Fu Qiumeng Fine Art is pleased to announce the solo exhibition of works by Chinese artist Fung Ming Chip (b. 1951) The Null Set ∅.

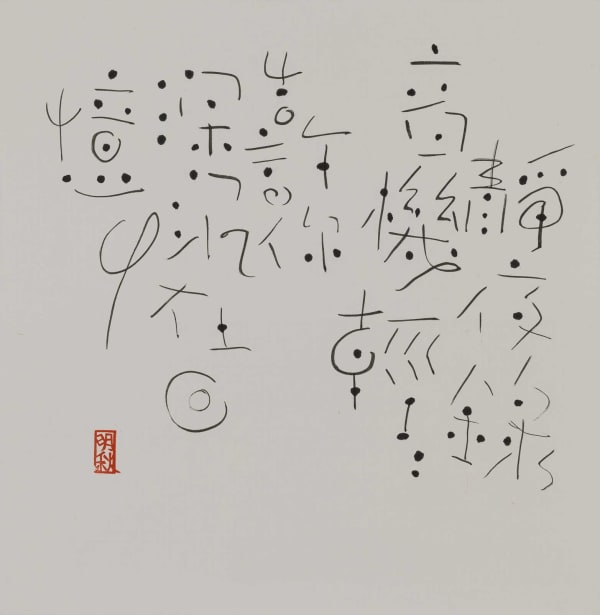

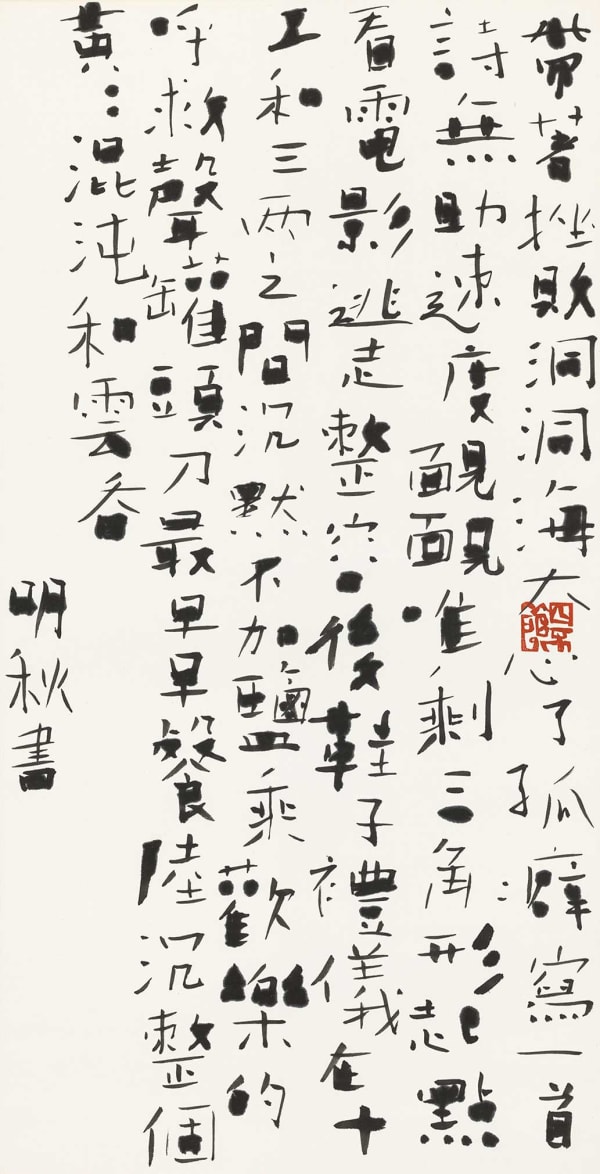

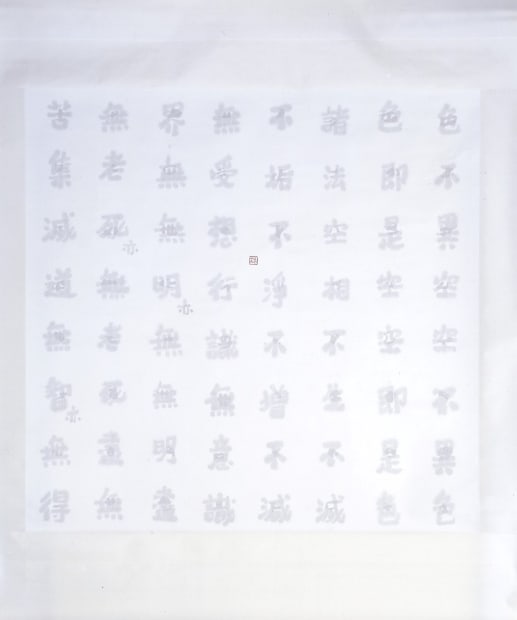

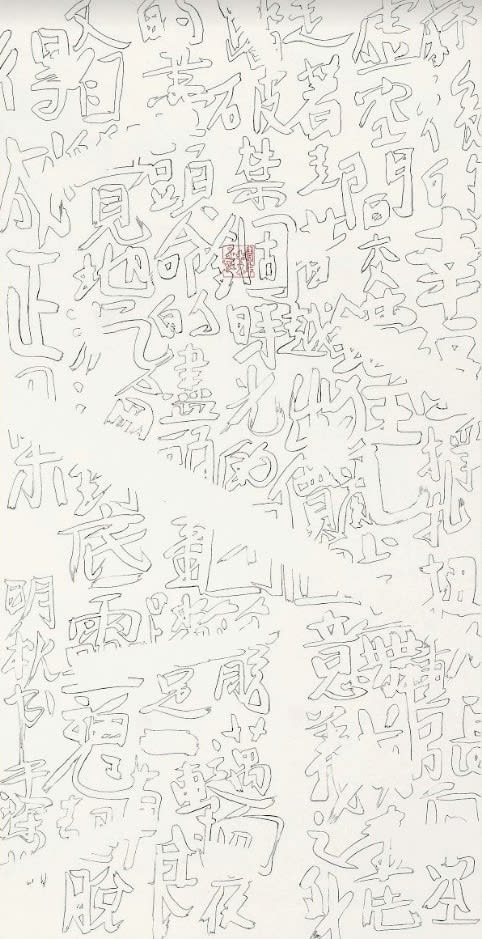

Fung mainly works with calligraphy and seal carving, reframing both through his conceptualization of space, time, and lines. By inventing scripts and writing procedures from ground up, Fung invites viewers to expand their understanding of calligraphy on various fronts. The writing of Fung’s scripts sometimes involves the use of new tools not traditionally associated with calligraphy; it sometimes requires Fung to rearrange the tools and materials of writing. In most of Fung’s calligraphic pieces, the characters verge between emergence and disappearance, veering in and out of the relief-like space demarcated by the xuan paper.