-

Introducing Chinese calligraphy to Western audiences has long been a challenge. The intricate beauty of the art is often overshadowed by a fundamental cultural and linguistic divide. While the meanings of the characters may be obscured by language barriers, this need not be an obstacle. Beyond the ability to read or understand Chinese characters lies a set of core principles—values that transcend language and allow this tradition that has lasted for more than two millennia to be appreciated by anyone willing to look closely.

-

-

Beyond “Calligraphy”

The common English translation “Chinese Calligraphy” only partially conveys the scope of the art form known as Shufa(書法), literally “the law of writing.” In English, calligraphy often refers to the decorative rendering of alphabetic letters, emphasizing beauty, legibility, and ornament. While this tradition has its own refinement and history, Shufa operates within a different framework. Rooted in Chinese characters—logographs that are at once visual, phonetic, and ideographic—Shufa integrates language, philosophy, and artistic expression in ways unique to the Chinese context. Each character compresses layers of meaning, functioning simultaneously as image, sound, and concept, a density of expression with no direct parallel in alphabetic systems.

Because of this unique foundation, different script styles reveal distinct dimensions of the tradition. Seal script (Zhuanshu 篆書), Clerical script (Lishu 隸書), and Regular script (Kaishu 楷書) are characterized by clarity, symmetry, and formal restraint. Each developed in contexts where authority, legibility, and durability were paramount—whether carved into stone, cast in bronze, or used for official documents. In these scripts, the emphasis lies on order and continuity, reflecting a cultural priority for stability and collective meaning over personal expression.

-

-

WANG TI 王禔 1880-1960Calligraphy Couplet in Seal Script 篆書六言聯, 1946ink on paper, a pair of hanging scrolls 水墨纸本 一对立轴39 1/2 x 8 1/2 in (2); 100.3 x 21.6 cm (2)

WANG TI 王禔 1880-1960Calligraphy Couplet in Seal Script 篆書六言聯, 1946ink on paper, a pair of hanging scrolls 水墨纸本 一对立轴39 1/2 x 8 1/2 in (2); 100.3 x 21.6 cm (2) -

By contrast, Running script (Xingshu 行書) and Cursive script (Caoshu 草書) open the door to personal expression. Here, the brush moves with greater freedom and vitality, allowing the artist’s rhythm, temperament, and inner energy to become vividly visible on the page. In these forms, Shufa transcends the idea of writing as decoration and becomes a living record of movement, thought, and spirit.

Therefore, "Shufa" is not best translated as "Chinese Calligraphy." It is both language and art, both communication and expression. Its most formal styles preserve cultural continuity and order, while its freer forms capture individuality and spirit in ways that resonate far beyond linguistic boundaries. To grasp how this duality operates in practice, we must return to the act of writing itself.

-

-

-

-

TRADITIONAL PAPER: THE UNFLINCHING WITNESS

Once the brush has gathered and directed this energy, it must be received somewhere—and here traditional Chinese paper plays a decisive role. These papers are crafted from the bark of trees such as blue sandalwood, paper mulberry, and mitsumata. Each material produces a distinct texture and level of absorbency, offering artists different surfaces with which to engage. The fibers are preserved in long strands, creating a structure that absorbs ink in subtle and complex ways. It is not only the surface texture but also the network of fibers within the sheet that interacts with liquid ink, shaping the saturation, spread, and edge of each stroke. The paper responds differently depending on the ink’s moisture and the pressure of the brush, producing a spectrum of effects—from crisp lines to layered, translucent shades of black that retain depth even when multiple strokes overlap.

Such paper allows no disguises. There are no erasures, no revisions, no second chances—only an unedited record of choice and nerve. Each stroke is preserved exactly as it was made, capturing the artist’s movement, energy, and state of mind in that instant. To write on this surface requires courage: once the brush touches the page, nothing can be undone. The artist must either prepare with clarity of intention or enter a state of focus so complete that hesitation has no place.

-

-

Jin Nong 金農 1687-1763Excerpt from The Rites of Zhou in Clerical Script 漆書節錄《周禮 · 夏官 · 職方氏》, 1750ink on paper, hanging scroll 水墨纸本 立轴47 x 15 1/2 in; 119.4 x 39.4 cm

Jin Nong 金農 1687-1763Excerpt from The Rites of Zhou in Clerical Script 漆書節錄《周禮 · 夏官 · 職方氏》, 1750ink on paper, hanging scroll 水墨纸本 立轴47 x 15 1/2 in; 119.4 x 39.4 cm -

Fung Ming ChipLight line: God/Devil 神魔光环学, 2002Ink on Paper 水墨纸本48 x 35 1/2 in

Fung Ming ChipLight line: God/Devil 神魔光环学, 2002Ink on Paper 水墨纸本48 x 35 1/2 in -

-

The Intangible Made Tangible: Using Qi to Understand Shufa

With brush and paper now joined, we can turn to the third and most elusive element: Qi. Through the centered brush, the artist transmits energy with precision, and through traditional paper, every nuance of that energy is faithfully preserved. It is from this union that the concept of Qi in calligraphy becomes comprehensible.

Although Qi is a complex concept in Chinese culture—often translated as “breath” or “vital energy”—within the practice of Shufa it can be understood more simply as the artist’s pulse, breath, or inner rhythm made visible on paper. The calligraphy brush, extremely soft and responsive, is typically held above the paper with the artist’s body suspended—no arm or wrist resting for support. The moment the tip touches the surface, it bends under pressure, producing lines of varying thickness and shape. These are not only the result of deliberate movements—lifting, pressing, and guiding the brush—but also of involuntary ones: the tremor of a hand, the cadence of breathing, subtle shifts in posture, and fluctuations of mood. Every stroke, then, is a composite of intention and accident, discipline and spontaneity. The brush becomes a sensitive instrument, recording not just motion but the flow of Qi.

To the casual viewer, the result may appear as two-dimensional lines of ink. To the trained eye, however, each stroke contains the full dimension of the artist’s being: traces of breathing rhythm, psychological state, reflexes for handling unexpected variations, even flashes of joy or intensity felt during the act of writing. In this sense, the stroke is less a fixed mark than a record of movement, a projection of lived experience onto paper.

-

Letters have long been one of the most important forms of Chinese calligraphy, embodying both artistic value and practical function. Unlike monumental inscriptions or works created specifically for display, letters emerged from everyday communication and thus preserve the most genuine and natural forms of brushwork. Some of the earliest surviving calligraphic masterpieces are in fact private letters, such as Lu Ji’s Pingfu Tie, Wang Xun’s Boyuan Tie, and Wang Xizhi’s Sangluan Tie. Though written for immediate and personal purposes, they have become timeless classics in the history of Chinese calligraphy.

The phrase “seeing the character is like seeing the person” finds its fullest expression in letters. Depending on the content, the writer unconsciously infuses the strokes with subtle and shifting emotions—joy, sorrow, urgency, or composure—feelings that the viewer can sense through the rhythm of the brush. Because letters were generally private and not composed for public display, they rarely exhibit the deliberate polish of formal calligraphy. Instead, they offer a direct reflection of the writer’s state of mind and bodily rhythm at the moment of writing. This uncontrived authenticity is among the most treasured qualities of the art.

Zhang Daqian’s letters continue this tradition. In his correspondence, brushwork becomes a vehicle for friendship and sincerity, with his personality flowing naturally between the lines. Compared with his more deliberate compositions on large-scale scrolls, his letters reveal a relaxed, unguarded side, embodying the notion that “calligraphy is the person.” In this way, letters are not only practical instruments of communication but also among the most immediate and heartfelt expressions within the art of Shufa, allowing us to encounter the living presence of the writer through ink on paper.

-

Wang Kaiyun 王闓運 1832-1916Shufa Couplet in Running ScriptInk on Paper, a pair of hanging scrolls 水墨纸本 一对立轴52 3/8 x 12 1/4 in; 133 x 31 cm

Wang Kaiyun 王闓運 1832-1916Shufa Couplet in Running ScriptInk on Paper, a pair of hanging scrolls 水墨纸本 一对立轴52 3/8 x 12 1/4 in; 133 x 31 cm -

-

C. C. Wang 王季迁Calligraphy Couplet 行书四言联Ink on Paper, a pair of hanging scrolls 水墨纸本 一对立轴49 1/2 x 14 1/2 in (2); 125.7 x 36.9 cm (2)

C. C. Wang 王季迁Calligraphy Couplet 行书四言联Ink on Paper, a pair of hanging scrolls 水墨纸本 一对立轴49 1/2 x 14 1/2 in (2); 125.7 x 36.9 cm (2) -

This group of works grew out of Wang Mansheng’s daily practice of Shufa, serving as a foundation for his long and thoughtful preparation of the exhibition Without Us. The poems perform a meditative allusion, guiding his reflection on the exhibition’s central question: how do we imagine a landscape without people? In Wang’s observations, the modern retina is flourished with the noise of industrial landscapes and artifacts, for which he seeks a tranquility in nature as a state of mind that allows transcendental engagement with the world he dwells in. Written on rustic papers made of tree bark, these quotidian accumulations embody a meditative process—each character flows consecutively like winds and waves across the page, carrying his pursuit of Wuren (无人, without us).

Wang interprets Wuren as a spontaneous oblivion of humanly desires through the practice of tranquility, which will ultimately dissolve his subjectivity in nature. With this being said, Shufa is an ideal medium for him to reach the state of mind. Beneath Wang’s writings sits a unitary form established upon archaic scripts. His characters sit steadily in blocks, with every stroke landing or standing with gravity, seeping through it the stoniness of seal and cleric scripts.

At their ends, Wang’s strokes spill from their volumes into the next, rebelling the limitations of form with the unraveled movement of nature. Yet his brush still runs as usual, embodying every touch of ink with tendons and bones that support the flesh, which through the writings one can picture a seated writer, injecting his full energy and spirituality onto the bare paper, maximizing his subjectivity while intentionally minimizing it.

-

For this reason, works of Shufa are often called “strokes of mind (Xinhua 心畫),” a term first articulated by Yang Xiong (53 BCE–18 CE) in Yangzi Fayan (Model Sayings of Master Yang 揚子法言). This does not suggest a literal transcription of thoughts, but an involuntary manifestation of the artist’s inner activity—mental, emotional, and physical—captured by the brush’s supple bristles.

In cursive script especially, this becomes strikingly clear. A single unbroken line may sweep across several characters, creating not only an unfiltered glimpse into the artist’s state of mind but also a visible measure of time itself: a duration inscribed in ink, flowing without pause until the movement comes to rest.

Therefore, as a synthesis of language, philosophy, and visual form, Shufa stands as one of China’s most complete cultural expressions—an art that unites technical mastery with millennia of aesthetic thought. It is at once image and text, abstraction and communication, a visual record of the artist’s energy, movement, and state of mind.

-

-

The aesthetic and expressive power of Shufa may be perceived independently of one’s ability to read Chinese. By following the arc of a stroke, sensing the breath within a line, and noticing the rhythm between ink and empty space, you enter the same current the artist once followed. At that moment, the work ceases to be bound by language. It becomes an encounter—direct, immediate, and human.

This exhibition invites you to experience Shufa in that spirit: not simply as writing, but as living art. To stand before these works is to glimpse a tradition that has shaped Chinese culture for millennia, yet still speaks with vitality today. Across distance and time, the movement of a hand continues to cross the divide, reminding us that art, at its deepest level, is nothing less than one soul reaching another.

-

-

Qian Feng 錢灃 1740-1795, Shufa Couplet in Running Script 行書七言聯

Qian Feng 錢灃 1740-1795, Shufa Couplet in Running Script 行書七言聯 -

Wang Kaiyun 王闓運 1832-1916, Shufa Couplet in Running Script

Wang Kaiyun 王闓運 1832-1916, Shufa Couplet in Running Script -

Shen Wei 沈衛 1862-1945, Shufa Couplet in Running Script

Shen Wei 沈衛 1862-1945, Shufa Couplet in Running Script -

Wang Fangyu, Ink (Muo) 墨, 1990

Wang Fangyu, Ink (Muo) 墨, 1990 -

Wang Fangyu, After Rain 雨过, 1982

Wang Fangyu, After Rain 雨过, 1982 -

Wang Fangyu, Ten thousand brushes, 1970

Wang Fangyu, Ten thousand brushes, 1970 -

Wang Fangyu, Dancing Calligraphy (Shu Wu) 书舞

Wang Fangyu, Dancing Calligraphy (Shu Wu) 书舞 -

Wang Mansheng, "Seven Joys" by Zhan Fangsheng 湛方生“七歡”, 2022

Wang Mansheng, "Seven Joys" by Zhan Fangsheng 湛方生“七歡”, 2022 -

Wang Mansheng, Xie Lingyun, Passing a Night on Mount Stone Gate 謝靈運《石门巖上宿》, 2022

Wang Mansheng, Xie Lingyun, Passing a Night on Mount Stone Gate 謝靈運《石门巖上宿》, 2022 -

Wang Mansheng, Sitting in Silence to Forget the Desires 靜坐在忘求, 2020

Wang Mansheng, Sitting in Silence to Forget the Desires 靜坐在忘求, 2020 -

Wang Mansheng, Wang Wei, My Garden by Riverside 王維“淇上即事田園”, 2022

Wang Mansheng, Wang Wei, My Garden by Riverside 王維“淇上即事田園”, 2022 -

Wang Mansheng, Farming, Tree-Planting, and Damming Streams South of the Estate 田南树园激流植楥 , 2020

Wang Mansheng, Farming, Tree-Planting, and Damming Streams South of the Estate 田南树园激流植楥 , 2020 -

Wang Mansheng, Golden Peaches 金桃, 2021

Wang Mansheng, Golden Peaches 金桃, 2021 -

Wang Mansheng, Plum Blossoms Fall 梅花落, 2018

Wang Mansheng, Plum Blossoms Fall 梅花落, 2018 -

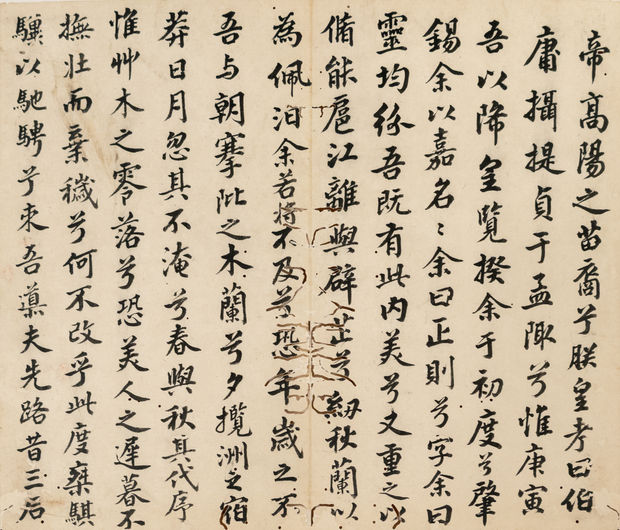

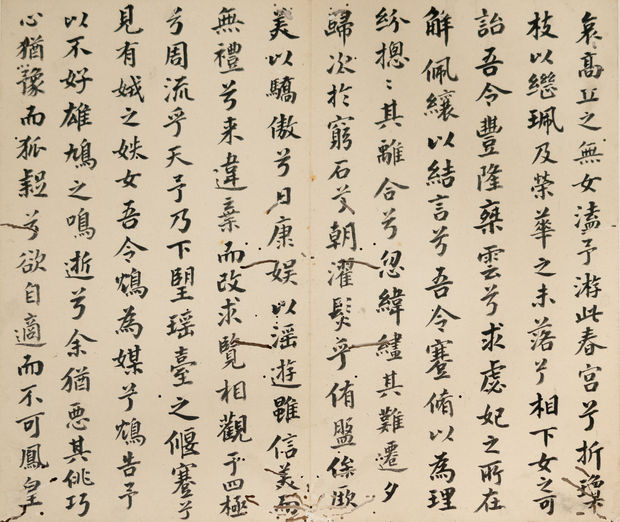

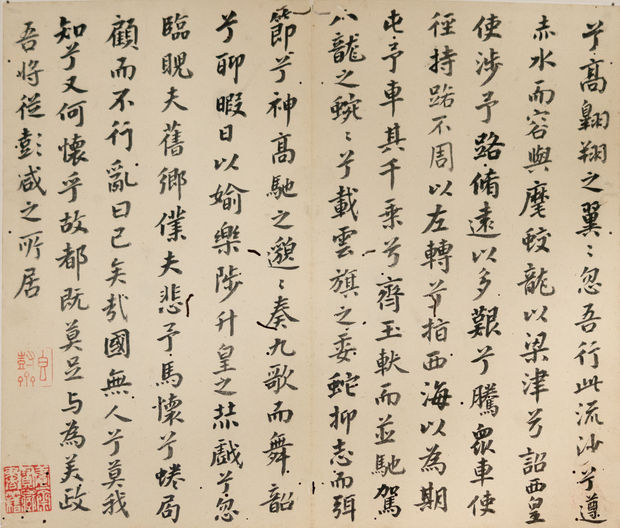

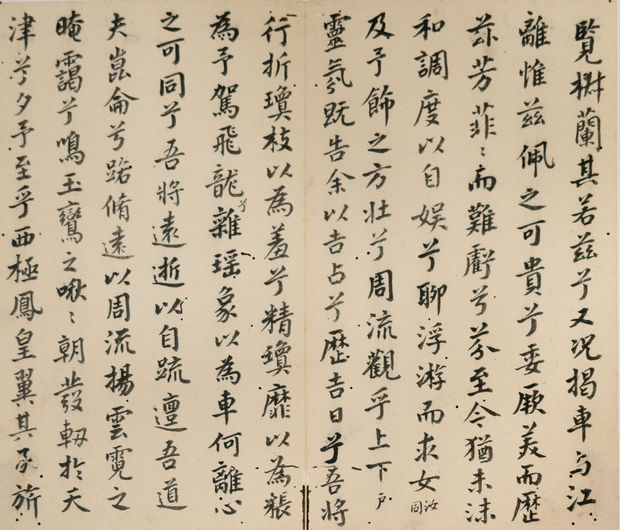

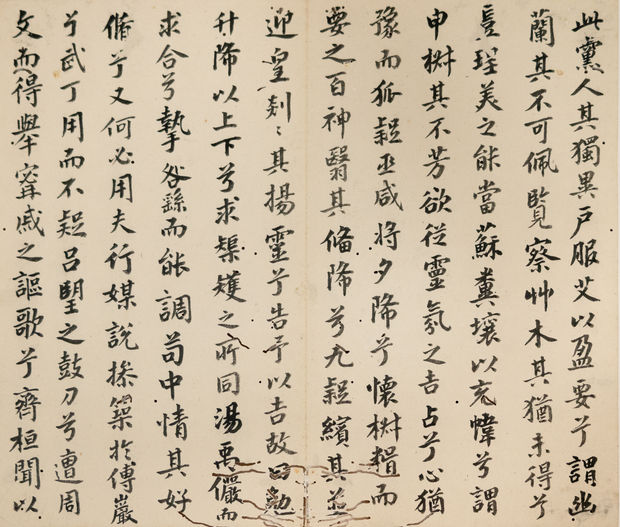

Qian Chenqun 錢陳群 1686-1774, Qu Yuan's Li Sao (Encountering Sorrow) in Running Script 行书《离骚》, 1759

Qian Chenqun 錢陳群 1686-1774, Qu Yuan's Li Sao (Encountering Sorrow) in Running Script 行书《离骚》, 1759 -

Wang Wenzhi 王文治 1730-1802, Poem in Running Script 题画诗

Wang Wenzhi 王文治 1730-1802, Poem in Running Script 题画诗 -

Fung Ming Chip, Light Line: God/Devil 神魔光环字, 2002

Fung Ming Chip, Light Line: God/Devil 神魔光环字, 2002 -

Fung Ming Chip, Transition Script, 变化字, 2022

Fung Ming Chip, Transition Script, 变化字, 2022 -

Zhang Tingji 张廷济 1768–1848, Excerpts from the Essays of Su Shi and Mi Fu in Running Script 行書蘇軾《柳十九帖》 , 1846

Zhang Tingji 张廷济 1768–1848, Excerpts from the Essays of Su Shi and Mi Fu in Running Script 行書蘇軾《柳十九帖》 , 1846 -

Yuanxi 元熙 Qing Dynasty, Calligraphy Excerpt of Yu Gonggong Stele 節臨《虞恭公碑》, 1873 or 1933

Yuanxi 元熙 Qing Dynasty, Calligraphy Excerpt of Yu Gonggong Stele 節臨《虞恭公碑》, 1873 or 1933 -

Wang Ti 王禔 1880-1960, Calligraphy Couplet in Seal Script 篆書六言聯, 1946

Wang Ti 王禔 1880-1960, Calligraphy Couplet in Seal Script 篆書六言聯, 1946 -

C. C. Wang 王季遷 1907-2003, Calligraphy Couplet 行书四言联

C. C. Wang 王季遷 1907-2003, Calligraphy Couplet 行书四言联 -

Jin Nong 金農 1687-1763, Excerpt from The Rites of Zhou in Clerical Script 漆書節錄《周禮 · 夏官 · 職方氏》, 1750

Jin Nong 金農 1687-1763, Excerpt from The Rites of Zhou in Clerical Script 漆書節錄《周禮 · 夏官 · 職方氏》, 1750 -

Zhang Daqian 張大千 1899-1983, Letter of Invitation to view the Blossoms

Zhang Daqian 張大千 1899-1983, Letter of Invitation to view the Blossoms -

Zhang Daqian 張大千 1899-1983, Letter of Travelling to New York

Zhang Daqian 張大千 1899-1983, Letter of Travelling to New York

-

11 September - 25 October 2025

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.