-

-

-

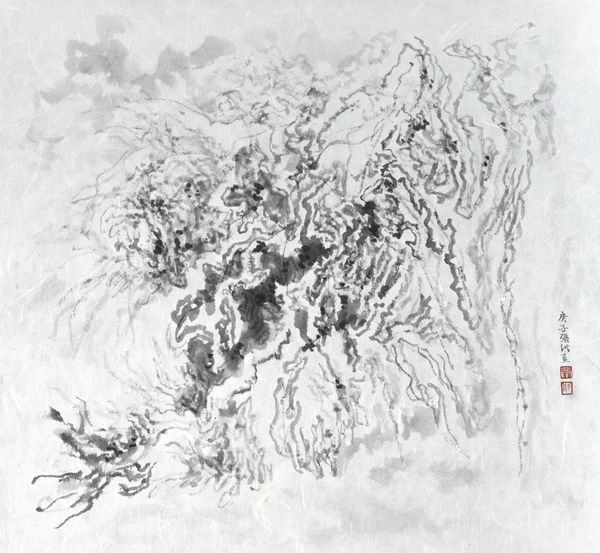

Figure 1. Arnold Chang.Kaleidoscopic Landscape 2014.03,2014.Erased pencil, ink and color on paper, 28 ½ x 56 ½ inches(72.4 x 143.5 cm).

Figure 1. Arnold Chang.Kaleidoscopic Landscape 2014.03,2014.Erased pencil, ink and color on paper, 28 ½ x 56 ½ inches(72.4 x 143.5 cm). -

Ten years later at Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, Chang now presents his first solo exhibition in New York since 1996, titled “The Mountains Show and Hide.” While Chang’s previous landscape paintings, created in the traditional Chinese literati manner, predominantly featured a monochromatic palette, this exhibition marks and introduces a ten-year exploration of incorporating color into his personal vision of landscape. This shift carries a significant meaning that western audiences may not immediately grasp, as color plays such a common and vital role in their practice and appreciation of art. In Chinese art history, by contrast, in most classical literati paintings color was often an afterthought that followed the forms defined through ink lines and washes. Chang’s experimentation with color as illustrated in the twenty exhibits here reflects his reimagining of the relationship between ink lines and flat color washes.

In his portrayal of landscapes, Chang treats ink lines and flat color washes as separate components and gives the two equal value. Here, color and ink work in tandem, creating monumental landscapes that resonate harmoniously yet retain a sense of independence from each other. Ink lines and color washes are seamlessly integrated in a multitude of ways. Sometimes lines act as borders, delineating blocks of color to differentiate the faces of multi-faced, bulbous mountain forms. In this case, color maintains its vibrancy within the lines, without necessarily being modulated like ink in monochromatic works.

-

In other instances, Chang applies spontaneous transparent color washes that cover certain lines, blending them into one organic whole. Alternatively, the interaction between ink lines and color washes may not perfectly align upon overlaying. This unexpected juxtaposition, however, results in more heightened vibrancy and visual resonance (Figure 2). In more realistic seasonal scenes, Chang also artfully places trees, plants, and other motifs in different colors amidst majestic peaks, inviting the audience into a trek across visual excitement and nuanced emotions, both conveyed through a juxtaposition of color patterns combined with the artist’s signature mode of subtle brushwork that resonates with the old masters (Figure 3). In some other imaginary and more abstract landscapes, which are disoriented by a seemingly incoherent spatial structure, Chang’s patterns of color combined with light ink washes are introduced to induce a dream-like milieu, where one may escape the chaos of contemporary life (Figure 4).

-

Chang’s approach is fundamentally art historical and intellectual. It has all evolved from his unique artistic background as an American-born-Chinese who grew up in New York City and is also a great synthesis of the amalgam of influences that he has encountered in various historical specificities. As is widely known, Chang’s artistic journey started with a deep immersion in traditional Chinese literati painting from his youth. He studied Chinese art history with Professor James Cahill and earned his master’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley (Figure 5). He subsequently befriended and studied ink painting with the eminent artist and collector C.C. Wang (1907-2003) for more than twenty-five years (Figure 6). Under the tutelage of Wang, whose collection of historical Chinese paintings was recognized as one of the greatest private collections in the world, Chang was given the rarest opportunity to study masterpieces up close and to faithfully copy these works, enabling him to absorb the most intricate nuances of bimo (traditional Chinese brush and ink) techniques and to internalize the brush idioms of the old masters for his own recreation of landscapes (Figure 7.1;7.2).

-

(Left) Figure 7.1. Dong Qichang (Chinese, 1555 - 1636), Landscape after Wang Meng. 1621-1624. Album leaf; ink and color on paper, 22 x 13 ¾ in (55.88 x 34.93 cm). Collection of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

(Right) Figure 7.2. Arnold Chang, Copy of an album leaf by Dong Qichang. n.d. Ink and Color on Paper, 24 ½ x 16 ¾ in (62.6 x 42.5 cm). Collection of Artist.

-

-

Figure 9. Detail. Arnold Chang.Landscape After Qiu Ying. Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 25 ½ x 23 ¼ in (64.8 x 59.1 cm). Private Collection.

Figure 9. Detail. Arnold Chang.Landscape After Qiu Ying. Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 25 ½ x 23 ¼ in (64.8 x 59.1 cm). Private Collection. -

-

Figure 11. Robert Kushner

Image Courtesy of Robert Kushner's official website

-

Figure 12. Mark Rothko. No.3/No.13,1949. Oil on Canvas, 71 ½ x 65 in (216.5 x 164.8 cm). Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Figure 12. Mark Rothko. No.3/No.13,1949. Oil on Canvas, 71 ½ x 65 in (216.5 x 164.8 cm). Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

-

Figure 16. C. C. Wang. no title (Abstract Work with Blue and Green), 1998. Ink and color on paper, 33 ¾ x 15 ⅝ inches (85.7 × 39.7 cm). Collection of Pao Yung Chao.

-

Figure 15. Arnold Chang, Landscape With Waterfalls 2020.07, 2020, ink and color on paper, 18 ½ x 28 ¾ in (46.7 x 73 cm)

Figure 15. Arnold Chang, Landscape With Waterfalls 2020.07, 2020, ink and color on paper, 18 ½ x 28 ¾ in (46.7 x 73 cm) -

Figure 18. Shitao (Chinese, 1642–1707).Wilderness Colors, 1700.Album of twelve paintings; ink and color on paper.Image (each leaf): 10 ⅞ x 9 ½ in. (27.6 x 24.1 cm). Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Figure 18. Shitao (Chinese, 1642–1707).Wilderness Colors, 1700.Album of twelve paintings; ink and color on paper.Image (each leaf): 10 ⅞ x 9 ½ in. (27.6 x 24.1 cm). Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. -

I introduce shan-se-you-wu-zhong (山色有无中), literally meaning the color of mountains between presence and absence, as an overarching theme for understanding Chang’s trajectory of his past-decade practice in color. It is a poetic line from Hanjiang lin tiao (A View of the Han River) composed by Wang Wei (699-759), one of the most distinguished painters and poets and the earliest literati artist in all of Chinese history. Transporting the audiences to the banks of the Han River, this line encapsulates the idea of perceiving the essence of landscape not only in its physical presence but also in its absence or even in the ambiguous space in between. This transient and transformative essence of landscape captured by Wang Wei is precisely what Chang’s artistic exploration of color combined with ink is all about. In his creations, mountains are simultaneously visible when ink lines and color washes represent landscapes, and invisible when color and line are used to emphasize formal qualities in their own right. Or one can enjoy a personal contemplation of the interplay between what is visible and what is not in his landscapes.

-

-

-

Arnold Chang, After Huang Gongwang 2020.03, 2020

Arnold Chang, After Huang Gongwang 2020.03, 2020 -

Arnold Chang, After Lu Zhi 2014.06, 2014

Arnold Chang, After Lu Zhi 2014.06, 2014 -

Arnold Chang, Autumn Landscape 2023.02, 2023

Arnold Chang, Autumn Landscape 2023.02, 2023 -

Arnold Chang, Autumn Sounds 2014.08, 2014

Arnold Chang, Autumn Sounds 2014.08, 2014 -

Arnold Chang, Boneless Landscape 2022.06, 2022

Arnold Chang, Boneless Landscape 2022.06, 2022 -

Arnold Chang, Colorado I, 2022

Arnold Chang, Colorado I, 2022 -

Arnold Chang, Colorado II, 2022

Arnold Chang, Colorado II, 2022 -

Arnold Chang, Ink Play 2020.12, 2020

Arnold Chang, Ink Play 2020.12, 2020 -

Arnold Chang, Kaleidoscopic Landscape 2014.03, 2014

Arnold Chang, Kaleidoscopic Landscape 2014.03, 2014 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2018.05, 2018

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2018.05, 2018 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2022.05, 2022

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2022.05, 2022 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.03, 2023

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.03, 2023 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.06, 2023

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.06, 2023 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.11, 2023

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.11, 2023 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape With Waterfalls 2020.07, 2020

Arnold Chang, Landscape With Waterfalls 2020.07, 2020 -

Arnold Chang, Snowscape 2024.01, 2024

Arnold Chang, Snowscape 2024.01, 2024 -

Arnold Chang, Untitled 2020.10, 2020

Arnold Chang, Untitled 2020.10, 2020 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.10, 2023

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.10, 2023 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.08, 2023

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2023.08, 2023 -

Arnold Chang, Summer 2018.03, 2018

Arnold Chang, Summer 2018.03, 2018 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape After Fang Congyi, 2020

Arnold Chang, Landscape After Fang Congyi, 2020 -

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2016.02, 2016

Arnold Chang, Landscape 2016.02, 2016 -

Arnold Chang, Cosmic Landscape , 2015

Arnold Chang, Cosmic Landscape , 2015

-

Curated by Joy Xiao Chen, 25 April - 22 June 2024

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.