-

-

折蘆為筆 Interview with Mansheng Wang

-

The exhibition is curated by Dr. Chao Ling (b. 1987), Assistant Professor in the Department of Chinese and History, City University of Hong Kong. Ling primarily researches classical Chinese poetry and art history, with a special focus on the medieval period. He also works on literary theory and philosophical investigations of the relationship between text and image. Ling holds a Ph. D. in East Asian Languages and Literatures from Yale University (2019) and B.A. in Chinese Languages and Literatures from Peking University (2009). An exhibition catalog will be published, in which his introductory essay will be included.

Wang’s painting and calligraphy have been exhibited worldwide and are in the permanent collection of museums, including the Brooklyn Museum, Baltimore Museum of Art, Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Princeton Art Museum, and Yale University Art Gallery. In China, he has shown his work at the Beijing Art Museum, Today Art Museum in Beijing, Xuhui Art Museum in Shanghai, and Shanxi Museum in Taiyuan. Wang has also lectured and given demonstrations on Chinese art and culture at universities and museums, including Columbia University, Harvard University, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York University, The New School, and Boston University. -

-

Moonlight on Stones

Author: Dr. Chao LingThe idea of moonlight on stones, when pondered philosophically with contemporary knowledge of physics, poses some intriguing questions. The visually perceivable reflected light on the stone is emitted certainly not from the moon, but the sun; when looking at the illuminated stone, we process the lit-up area as an effect of moonlight based on comparison with the picture of sunshine registered in our mind. If we suspend this concern, the next issue is this: how can we say that the moonlight is on the stone, while physically speaking, it is after all a brighter part of the stone. These two issues both reveal the idea of presenting a world view in a seemingly representational mode, which in my opinion, highlights the intellectual robustness of Wang Mansheng’s (b. 1962) artwork. Several words came to my mind—translation, transmedium, and transforming–when I started closely looking at these pictures. The paintings try to signal and imply some deeper ideas which are inspired by appreciation of nature and then further developed in the process of artistic production. The paintings on view theoretically join, in a visual language, the polyphonic conversation with Kantian scaffolding, German idealism, Spinozist mode, and the Chinese tradition of the transcendental dao (way, principle, etc.) manifested in the mundane physical world—a physically metaphysical experiment.

-

-

-

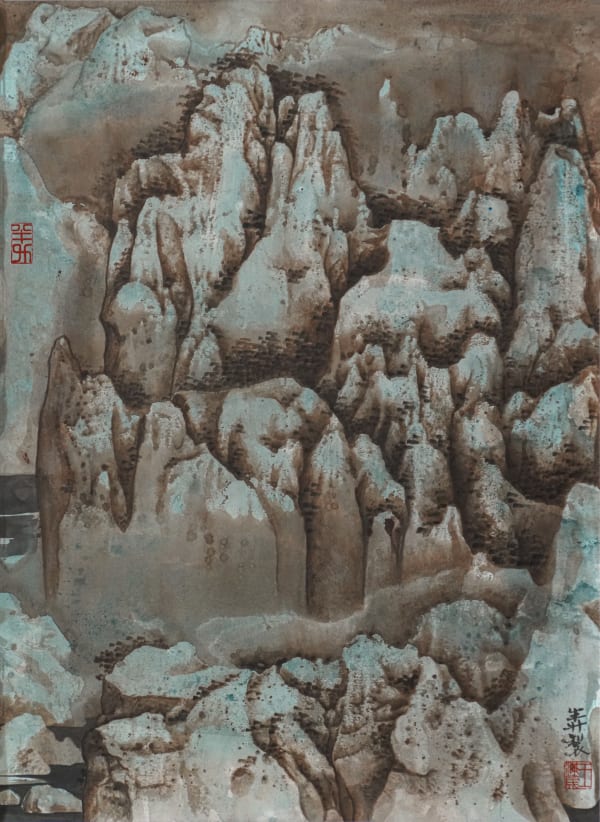

Wang Mansheng, Stone Gate Cliff Lodge, 2009, Ink, Walnut Ink, Tempera, Acrylic on Paper. 30 × 22 in (76.2 × 55.9 cm).

-

-

Installation view of the exhibition: "Moonlight on Stones."

Installation view of the exhibition: "Moonlight on Stones."Xie Lingyun was maybe the first landscape poet who devoutly invites the readers to see the landscape through a philosophical lens. For instance, in his “Fuchun Isle” 富春渚詩, he wrote: “When things come continuously one should become used to them; in doubled mountains, what is valuable is stopping and lodging.” (洊至宜便習,兼山貴止託。) Xie Lingyun looks at the continuously flowing water and the constant encounter with mountains, and what he sees is not nature but a text. He sees the Kan 坎 (water) hexagram of two Kan trigrams put together, and the Gen 艮 (mountain) hexagram of two mountain trigrams repeated. This way of reading is mainly based on knowledge of past texts. And this way of seeing a mountain was made possible by the emergence of the Dark Learning (xuanxue 玄學). The materiality of things was sacrificed to their textuality. One should receive enlightenment, or at least pursue the metaphysical principles.

-

"Different tones altogether reach hearing,

Unique sounds are all pure and elevated.

異音同致聽,殊嚮俱清越。"

“Stone Gate Cliff Lodge” was written in the autumn of 430, when Xie started his second reclusive retreat to his hometown. The caption is the opening two couplets. The first couplet laments the transience and vulnerability of orchids. As the time of the day moved from morning to evening, the poet retreated to a lofty residence, where he began to playfully contemplate the moonlight shed on the rocks. Was the poet suggesting that there is something more permanent than the organic components of nature in the moonlight? Or were they equally transient yet both revealing something eternal? The fourth couplet of the poem implies the latter. It reads:

-

-

Even though myriad things vary in physical presentation, they embody universal law and can influence human beings in the same manner. A Qing critic of poetry Wang Fuzhi 王夫之 (1619–1692) commented on this poem: “[The entire poem] turns into one piece, just like a full moon with light—having no contour lines 轉成一片,如滿月含光,都無輪廓.”

Capturing the poetic aesthetics of vague moonlight on rigid rocks, Wang’s image introduces a contrast between mountain boulders, contoured in lines, and moonlight, ink washes without clear borders. In a rather straightforward way, he evokes the world of yin and yang, just like Xie Lingyun skillfully demonstrated.

The poetic exposition of the dao echoes Wang’s philosophy of painting landscapes. He travels extensively around the globe and the US to observe real mountains and rivers. Just like Shitao 石濤 (1642–1707), who “made drafts after exhausting eccentric peaks 搜盡奇峰打草稿,” Wang visits states like Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona, and the alps in the Switzerland, among many other spectacular mountains, not to represent them realistically, but to extract the mountain-ness of all mountains. The way of representing mountain bodies is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese landscape paintings; the method of combining life sketching with imaginary textures is a collective practice of western and eastern methodologies; the understanding of the essential form of mountains is achieved in a global experience.

-

Wang Mansheng, Poem of Roving in the Mountains, 2016, Ink, Walnut Ink, Acrylic on Paper, 22 × 30 in (55.9 × 76.2 cm)

-

-

Detail of Wang Mansheng, Stone Gate Cliff Lodge.

-

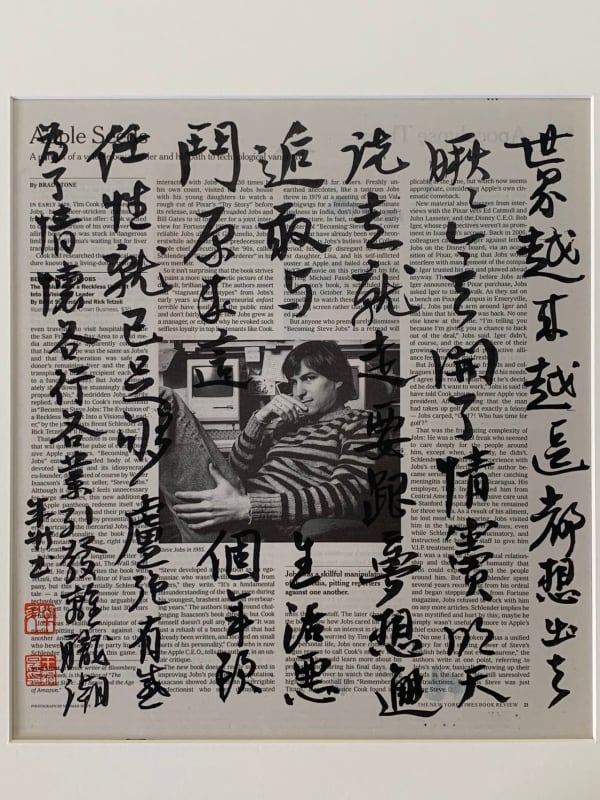

Writing characters on mountains or steles is a common form of commemoration–an act of marking permanent traces on an unclaimed surface, in many parts of the world. In the Chinese tradition, inscribing texts on mountain cliffs is not only a commemorative act of monumentality, but also an important calligraphic art. Wang Mansheng is also a disciplined student of calligraphy who copies copybooks and rubbings of inscriptions diligently while also exploring a self-expressive style of writing. When he practices, he sometimes simply grabs a sheet of saved local or national newspaper–covered by printed English letters telling stories of the daily world, and writes on them calligraphy in different scripts and sizes. The painter probably did not think in calligraphic terms during the process of producing the “Night Mountain”, but the calligraphic aesthetic which purely depends on lines, shapes, spacing and shades of ink trained the artist’s hands and eyes. Moreover, the symbolic act of adding text to landscapes—carving an inscription on mountains or adding a poetic colophon/caption/inscription to paintings, reminds viewers that the artist intends to use a specific image to illustrate the general concept of landscape.

-

-

II.

Chinese landscape poetry is often related to the topic of becoming a Daoist immortal who, upon enlightenment, flies up to the heavens or mythical high mountains to enjoy eternal life. The deep mountains have layers of heavily vegetated peaks, so high up that they touch the heavens and mountain dwellers would forget about time passing.

As the first section has shown, if the purpose of Wang’s landscape painting largely is to visually embody the ultimate dao, echoing the poetic tradition, then what does the human (artist’s) body do in this process? Is he simply a craftsman, a technician, or an important cauldron that forges and creates such transcendental knowledge? There is an outstanding painting with a profound poetic caption in this exhibition, which deals with this topic.

-

-

Qiu Chuji (1149–1227) was a famous Daoist priest of the sect of Complete Perfection 全真教. He is known for meeting Genghis Khan near the Hindu Kush. His disciple put together the narrative of his expedition, Travels to the West of Qiu Chang Chun, in which we can find vivid descriptions of nature and people. The quoted line is embedded in a series of realistic landscape depictions. However, it is precisely the artist’s act of isolating a single couplet and attaching it to the image that calls our attention to the idea of the Daoist internal cinnabar, or neidan 内丹. Drawing its theoretical foundation from the Eastern Han text, Cantong qi 參同契, the theory of internal cinnabar believes that the human body is a cauldron that, with the circulation of primordial qi, could fire up internal cinnabar that allows the practitioner to achieve immortality. Such a theory began to be systemized in the Northern Song dynasty and became an important aspect of the Complete Perfection teachings. In order to be successful in internal cinnabar firing, it is crucial for the practitioner in meditation to be able to use internal visualization 內觀 to see the internal vision/landscape 內景.

-

Neijingtu. published in 1886. Neidan 384 NeijingTu1

-

-

-

Wang Mansheng, Reed Brush to Paint Ancient Pine, 2016, Ink on Paper, 27 × 39 in (68.6 × 99.1 cm).

-

-

Wang Mansheng, Climbing Incense Burner Peak, 2021

Wang Mansheng, Climbing Incense Burner Peak, 2021 -

Wang Mansheng, Calling the Recluse 招隱詩, 2009

Wang Mansheng, Calling the Recluse 招隱詩, 2009 -

Wang Mansheng, Calling the Recluse by Lu Ji, 2013

Wang Mansheng, Calling the Recluse by Lu Ji, 2013 -

Wang Mansheng, At Night, Going out from Western Archery Hall, 2021

Wang Mansheng, At Night, Going out from Western Archery Hall, 2021 -

Wang Mansheng, Deep in the Mountains Searching for Ancient Trees No. 5, 2014

Wang Mansheng, Deep in the Mountains Searching for Ancient Trees No. 5, 2014 -

Wang Mansheng, Diary of Travels West of Changchun Zhenren 長春真人西遊記, 2013

Wang Mansheng, Diary of Travels West of Changchun Zhenren 長春真人西遊記, 2013 -

Wang Mansheng, Gazing at Mt. Lu’s Waterfall Springs from Hukou, 2013

Wang Mansheng, Gazing at Mt. Lu’s Waterfall Springs from Hukou, 2013 -

Wang Mansheng, Gazing North Toward Mt. Su Dan 北望蘇耽山, 2013

Wang Mansheng, Gazing North Toward Mt. Su Dan 北望蘇耽山, 2013 -

![Wang Mansheng, High hills rising to graceful peaks,From afar, all are marvelous. Tao Yuanming (c. 365—427) Matching [a verse] by Registrar Guo, 2017](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Wang Mansheng, High hills rising to graceful peaks,From afar, all are marvelous. Tao Yuanming (c. 365—427) Matching [a verse] by Registrar Guo, 2017

Wang Mansheng, High hills rising to graceful peaks,From afar, all are marvelous. Tao Yuanming (c. 365—427) Matching [a verse] by Registrar Guo, 2017 -

Wang Mansheng, Playing with the Moon at Eastern Creek, 2015

Wang Mansheng, Playing with the Moon at Eastern Creek, 2015 -

Wang Mansheng, Poem of Roving in the Mountains, 2009

Wang Mansheng, Poem of Roving in the Mountains, 2009 -

Wang Mansheng, Reed Brush to Paint Ancient Pine, 2016

Wang Mansheng, Reed Brush to Paint Ancient Pine, 2016 -

Wang Mansheng, Poem on the Newspaper, 2018

Wang Mansheng, Poem on the Newspaper, 2018 -

Wang Mansheng, Remaining Snow, 2010

Wang Mansheng, Remaining Snow, 2010 -

Wang Mansheng, Responding to Yan Gong, 2013

Wang Mansheng, Responding to Yan Gong, 2013 -

Wang Mansheng, Rocks on Travels Down the Gan River 下灨石, 2013

Wang Mansheng, Rocks on Travels Down the Gan River 下灨石, 2013 -

Wang Mansheng, Roving While Reclining, 2022

Wang Mansheng, Roving While Reclining, 2022 -

Wang Mansheng, Searching for Master Yong’s Hermitage, 2009

Wang Mansheng, Searching for Master Yong’s Hermitage, 2009 -

Wang Mansheng, Stone Gate Cliff Lodge 石門巖上宿, 2009

Wang Mansheng, Stone Gate Cliff Lodge 石門巖上宿, 2009 -

Wang Mansheng, Wanting a poem without sound, 2017

Wang Mansheng, Wanting a poem without sound, 2017 -

Wang Mansheng, Summer Shade, 2018

Wang Mansheng, Summer Shade, 2018 -

Wang Mansheng, Watching a South Mountain Evening, 2015

Wang Mansheng, Watching a South Mountain Evening, 2015

-

-

Wang Mansheng

About Artist

Curated by Dr. Chao Ling, 20 May - 23 July 2022

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.

![Wang Mansheng, High hills rising to graceful peaks,From afar, all are marvelous. Tao Yuanming (c. 365—427) Matching [a verse] by Registrar Guo, 2017](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/fuqiumengfineartllc/images/view/d818a4a18387141cb8cf6dbbe15db088/fuqiumengfineart-wang-mansheng-high-hills-rising-to-graceful-peaks-from-afar-all-are-marvelous.-tao-yuanming-c.-365-427-matching-a-verse-by-registrar-guo-2017.jpg)