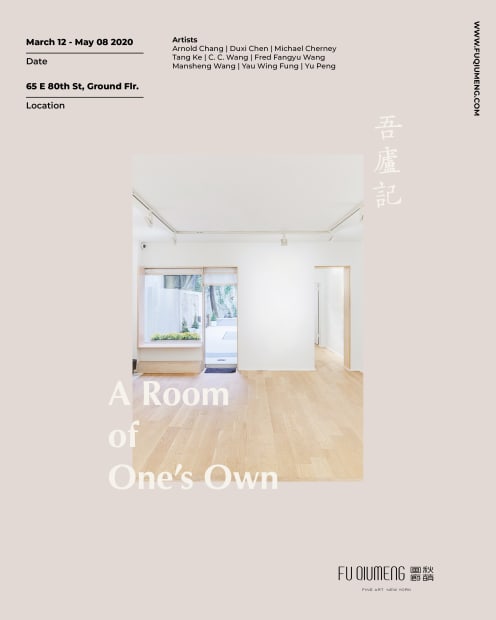

Fu Qiumeng Fine Art is pleased to announce the opening of our new show A Room of One’s Own, which will be exhibiting during Asia Week New York. By showing works in the format of hanging scroll, album leaves, fan, and handscroll, the exhibition focuses on modes of viewing specific to Chinese painting and calligraphy. It includes traditional artworks, as well as contemporary works by Arnold Chang (b. 1954), Michael Cherney (b. 1969), Tai Xiangzhou (b.1968), Tang Ke (b. 1972), C. C. Wang (1907–2003), Fred Fangyu Wang (1913–1997), Mansheng Wang (b. 1962), Yau Wing Fung (b. 1990) , and Yu Peng (1955-2014). To fully convey the visuality of traditional artworks, we have made specific arrangements to let visitors approach these works on a one-to-one basis. Viewers are also welcome to unfold the handscroll, look through the album leaves, and hold the fans in their hands. On April, viewers are invited to closely examine the artworks and enjoy a cup of tea with an artist. A Room of One’s Own will be on view at 65 East 80th Street.

-

-

-

For this exhibition, we aim to create a semi-private space that facilitates communication with people of sympathetic minds. Our idea is inspired by the mode of social interaction between Chinese literati. Since the Song Dynasty, most literati artists were scholar-officials. Quite different from the myth of artist as an eccentric, scholar-officials occupy a central position in the society. They are bureaucrats in charge of political affairs in the state administration, degreed intellectuals selected through a civil service exam, and erudite scholars who set the tone of contemporary culture. While people tend to associate the role of scholar-official with social prestige, a recurrent theme of literati art is reclusion, the voluntary choice of withdrawing from the society. While earlier literati took this decision to keep themselves away from hostile situations, under the influence of Buddhism and Taoism, people started to associate reclusion with a love for nature and a search for unstrained freedom from worldly affairs during the third and fourth centuries. Seemingly opposite, action and withdrawal constitute two critical aspects of scholar-officials’ intellectual life.

-

-

-

These trends underscore the importance of private viewing in Chinese art. Hanging scrolls, for example, were mostly rolled up, kept in wooden boxes, and were only taken out for viewing from time to time. Album leaves, handscroll, and fan are among the most intimate formats of Chinese painting. Album leaves are a series of small-sized images assembled by an artist or collector. Handscrolls are usually about the same height as album leaves (about ten inches), yet they are much longer (may reach more than ten feet in length). Fan paintings are meant for folding or rigid fans. The viewing of these three kinds of artworks all entails holding the artworks in hands. Handscroll, in particular, is to be unfolded from right to left and viewed section by section. The ways in which these works were mounted, displayed, and handled affect how people read these artworks.