The delicate Paphiopedilum sanderianum, the hanging mysore clockvine, the withered delphiniums —— Artist Benjamin Langford uses digital prints on canvas to create large-scale illusionistic flowers that explore the ways in which technology brings us closer to nature through increasingly vivid modes of representation, while distorting our sense of the real. Moving between virtuality and substantiality, artificial and natural, real and surreal, allows Lang- ford to incorporate the relationship between technology and nature into his flower works.

Langford was obsessed with flowers, and has collected carnivorous plants since he was a child. “The more alien and rare a plant was, the more I was interested”, Langford said in an interview. For example, plants like Rafflesia and Titan Arum, which both have strange relationships to animals and unusual life cycles, were always his favorite. These flowers have evolved over hundreds of years to be better at luring insects, and although humans are not their target, we can’t help but be drawn to their strange appearance. For Langford, the idea that flowers are a structure that has evolved specifically for its ability to attract animals, has led to an interest in examining our own relationship to flowers and the relationship between flowers and art. Langford’s childhood also reveals early influences that have drawn him to an affection towards flowers. Born in Connecticut, USA, his mother used to do gardening in the backyard of his home since he remembered. When he grew up, he lived in London and Singapore, where there is a strong gardening culture. Because of the different climates in differ- ent places, he could also see many different plants. Flowers seem to have never been absent during Langford’s upbringing.

“The more alien and rare a plant was, the more I was interested.”

—— Benjamin Langford

Flowers

Langford’s strong affection for flowers is also directly reflected in his works, and flowers have be-come the frequent subjects of his creation. When asked why the flowers were enlarged so dramatically, Langford replied that these large-scale flower sculptures were his exploration of real and surreal. The virtual illusion they create is realistic from a distance, but the viewer knows that the object they are looking at is actually a 2D image. When the viewer is tricked by the surreal scenes presented by these flower sculptures, their size and materiality itself will immediately bring the viewer back to reality.

When talking about why such a large flower sculpture was made, Langford regarded the large size as a means to exaggerate its illusion. From a certain perspective, these works can also be seen as a witty parody or détournement (a method of reusing the old elements of mainstream media to carry out subversive creation). They are no longer manifestations of flowers but become objects themselves. And after zooming in, more details of the flowers can be reflected, and viewers can appreciate from a new perspective.

Q&A

Q: What do you think is the relationship between your Flowers and space? Do you think it is photography or sculpture?

A: The Flowers exist in a funny gray area spatially; because they do not conform to a traditional photographic frame, they trick the eye into seeing the photographic space as physical textures rather than as a window. The illusion really only holds up from a distance though, when viewed closer, it is easy to see the flatness of the image. Yet the way they are hung, the material curls and bends in a sculptural way–similar to a soft sculpture. Ultimately I consider them sculptures, because I think of them similarly to relief sculptures, where two-dimensional techniques and three-dimensional forms interact to create a unique perception of space.

Q: In your Flowers installation, I see a bit of a juxtaposition between the concrete, which is the material itself, and their motion, which are the vitality of flowers. Were you intentionally trying to create such tension?

A: Yes, I think the tension between the material and the vitality of the imagery is interesting. I think it brings to attention the limitations of photography and images in general. Images have a way of animating and actually seeming to breathe life into inanimate objects; and, their capacity for detail can achieve a clarity that goes beyond what our eyes can see.

In a way, my Flowers can feel more alive than experiencing the original flower in person, yet their materiality feels strangely out of reach. Images depend upon hiding their own materiality to really hypnotize us and make us feel that we are seeing reality. My Flowers try to treat the immaterial surface of an image like it is a sculptural material which brings this contrast to attention. They feel intensely alive yet also, in a way, absent.

Q: This is your first outdoor installation, which is different from your previous exhibition. What’re your thoughts on putting your artworks around the real plants in the garden this time?

A: I’m so excited to be showing my first outdoor works! I think the interaction of plant life and the sculptures is really fascinating; my favorite moment is the dangling ivy that partially obscures Daffodil. I think what appeals to me about the interaction (which will only become more apparent over time) is the sense that these giant synthetic representations of nature seem to be gradually overcome by the elements and plants around them. To me it seems like a process is going full-circle– they’ll slowly become more weathered and really merge with the plants around them, if they are given enough time.

In the Greenhouse

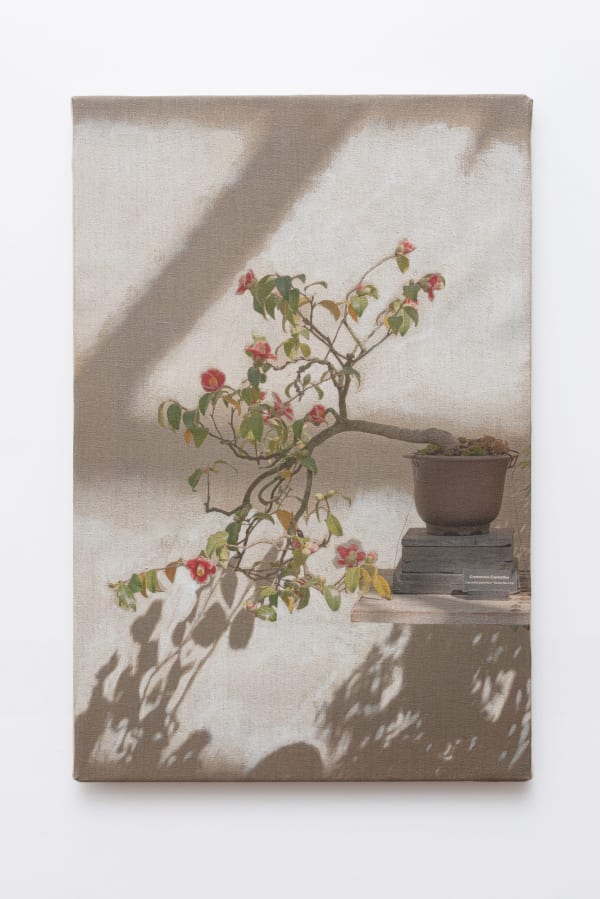

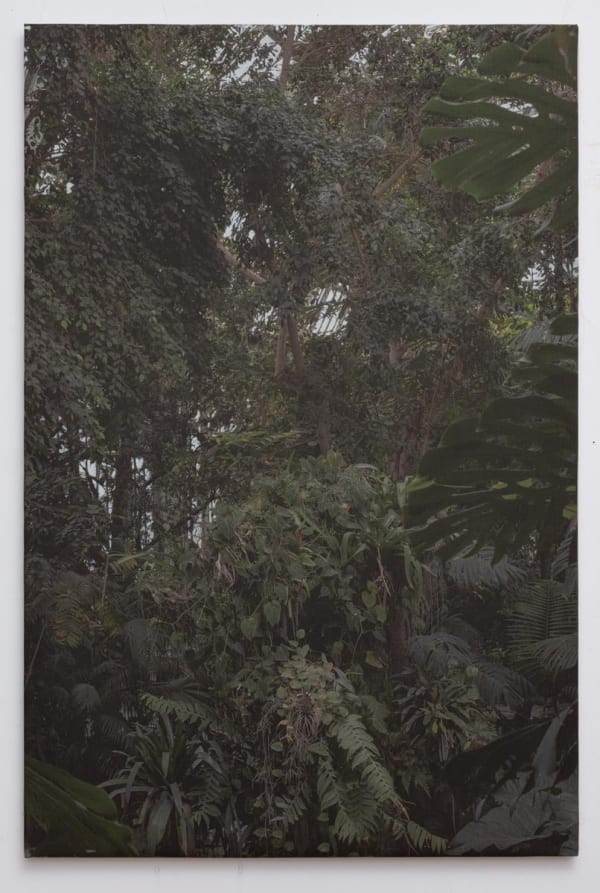

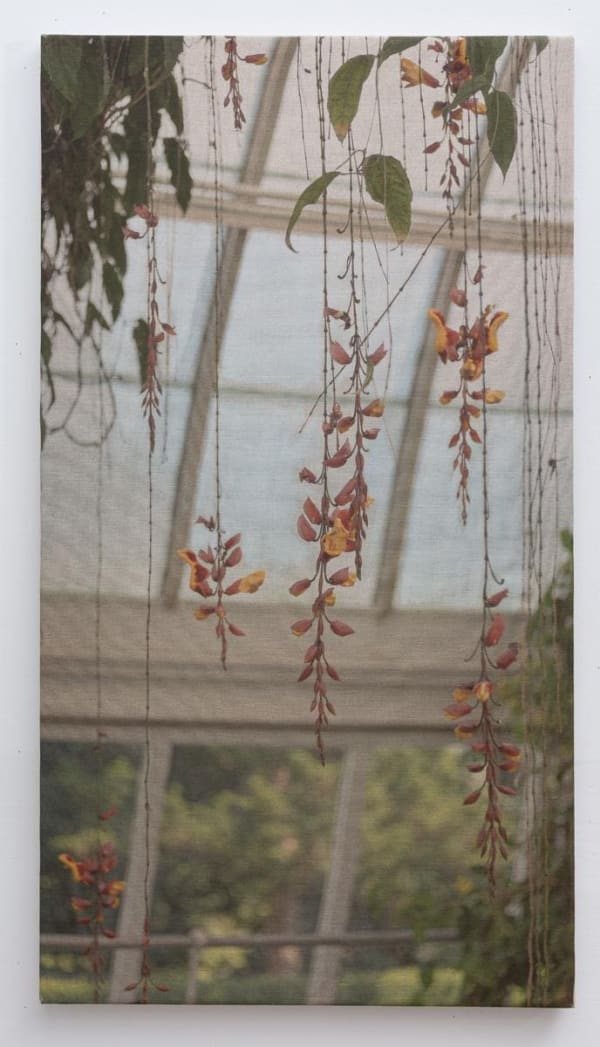

Different from his large-scale flowers, Langford’s new series, In the Greenhouse, is being exhibited for the first time. Compared with the fantasy exaggeration of the “Flowers”, this series of work has a tranquil and poetic atmosphere. He combines the use of digital printing and hand-painting on raw linen to explore the greenhouse as a metaphoric space. By pairing the natural, old-world materiality of raw linen with the use of digital technologies — these works invoke a sense of being misplaced in time: hoving between pre-modern painting traditions and digital imaging.

This series of work is intended to show the beauty of nature and the sense of artificial imprisonment reflected by the metals while the scenes taken by the artist are not staged or modeled. Langford would shoot from a certain perspective to capture the ideal image. He would travel around different places to find the “greenhouse” he wanted. Hence the metaphorical idea presented weighs more than the geological location of the greenhouse.

Q&A

Q: What does “In the Greenhouse” mean to you? How are those ideas expressed in this artwork?

A: My newest series, In the Greenhouse, explores the idea of a greenhouse as a metaphoric space. Many of the larger works of the series upon first glance look like an image of a deep, dense jungle, a foreboding place you could get lost in: there isn’t any sense of a path or trail through the foliage. Upon closer inspection, the viewer can see the geometry of steel and glass in the glimmers of light that peek through the trees. I find this idea very evocative. A space that presents itself as a dense, natural wilderness, but is, in fact, a place that is controlled and enclosed: a simulated jungle.

They’re somewhat dystopic images– they allude to a world where untouched wilderness is an illusion — where nature is represented, but no longer exists in an unadulterated form. None of the images in the series ever leave the space of the Greenhouse. It gives a sense of being trapped in this world of a false nature. At the same time, there is something very seductive about the space. They have an unnatural sense of quiet and there is an enveloping darkness to the foliage.

The other part of this series are the smaller works– two of which are showing in the show at Fu Qiumeng. These works act as details in this imagined Greenhouse. They focus on sometimes picturesque moments like delicate dangling flowers or a “wind-swept” bonsai that looks like it could be a tree found clinging off a misty mountainside. Yet, these details also allude to this sense of containment: the rigid framing of the greenhouse windows and the geometric shadows they cast are highlighted along with supports, signage, and infrastructure used to present these natural specimens. The series explores this push and pull between natural beauty and human control

Q: What is the hardest part of creating these works?

A: With the “In the Greenhouse” series, the hardest part for me is the editing process– selecting which images evoke the mood and atmosphere that I want to create with the series. I am also hand-painting certain elements within the images; this took some trial and error to figure out. It is easy to be heavy-handed when mixing hand-painting and photo-graphic imagery; but, I feel that I know where the limits are, where my hand blends seamlessly into the image. The combination of these two techniques also create a poetic atmosphere.

After a year of exploration, the variations in Lang- ford’s work and his approach have continued with the same themes he has been exploring, but with a different approach that draws his thoughts on “flowers” and “nature” into a broader context.