Living in solitary to attain the ambition, practicing righteousness to carry out the principles

Madame Figaro invited Fu Qiumeng to write a column about classical Chinese culture. In her article, Fu talks about how artists of the ancient and contemporary periods address the theme of reclusion, a classical theme in Chinese literati culture. She contextualizes this theme with the philosophy of Confucianism and Daoism. Based on this framework, she compares two sets of paintings—Wu Zhen’s Fisherman (《芦滩钓艇图》) (ca. 1530) and two photographs from Michael Cherney’s series Eight Views of the Xiao Xiang (Eight Views of the Xiao Xiang- Fishing Village in Evening Glow《潇湘八景之渔村落照》(2008–2009) and Eight Views of the Xiao Xiang-Mountain Market, Clearing Mist《潇湘八景之山市晴岚》(2008–2009)), Bada Shanren’s Simple and Solitary(《古澹萧寥》)(1864) and Yau Wing Fung’s Mirage VI (《蜃境–六》) (2019). According to Fu, reclusion does not necessarily mean the separation from society. Rather, it can be a gesture of resistance. By taking one step back, literati may find a profound way of connecting with their mind and nature, which inspires their cultural production in various forms.

Introduction

Heaven, Earth, and I were produced together, and all things and I are one.

The ancient and modern transmutation of the motif of ``Fisherman``

Wu Zheng, "Fisherman", Ink on Paper, 31.1 cm × 53.8 cm,ca. 1350

Literati painting or scholar painting is the dominant art genre in Chinese classical art history, it embodies four elements of value: character, learning, talent and thinking. Such aesthetic values emerged in the Tang and Song Dynasties and later developed in the Yuan Dynasty which is the first dynasty in Chinese history to be ruled by a foreign nation. The Mongolian rulers executed brutal repression of the Han nation people in order to consolidate their political power, and the strict hierarchy and loss of national belonging forced many literati and scholars to live in seclusion and under the circumstances of the fallen state. Wu Zhen (1280-1354), one of the “Four Masters in the Yuan dynasty” along with Huang Gongwang, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng, was one of them.

Wu Zhen, or Zhonggui and “Plum blossom Daoist,” was a scholar, poet, calligrapher, landscape painter. He was a high moral character who chose to live in seclusion. Among his landscape paintings are many subjects about fishermen and other hermit stories. This painting, “Fisherman”, depicts a peaceful scene of a fisherman returning home with subtle and minimal brushwork. In the painter’s brush strokes, as the strokes iterate or extend, the branches and leaves of the lush jungle spread out on the rocky, seemingly undulating with the breeze. With the painter’s delicate and relaxed lines, the water waves under the shade of the trees slowly connect a boat and a fisherman, and then the line of sight is pointed to the endless sky and then we see a poem, “Red leaves in the west village reflect the evening rays, Yellow reeds on a sandy bank cast early moon shadows. Lightly stirring his oar, thinking of returning home, he puts aside his fishing pole, and will catch no more. The old Plum Blossom played with the ink. ”

Michael Chenery

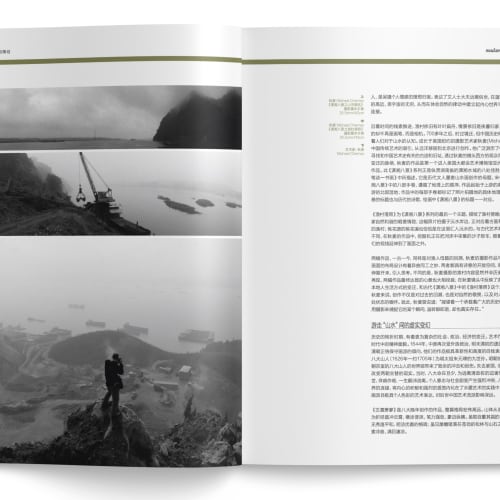

Michael Cherney,"Eight Views of Xiao Xiang Fishing Village in Evening Glow " , 28°47'39" N, 111°25'41” E,photography in scoll ,25.5 cm x 142 cm,2008-2009

Wu Zhen’s treatment of the picture has an open layout which is similar to the literati’s poetry, and the excesses between the brush strokes are powerful and dashing, giving the viewer a quiet and calm imagination. The fisherman in the harmony of nature is the ideal home for Wu Zhen’s personal emotions. It expresses that the literati and scholars are isolated from the mundane world, looking at the lofty sky and thinking about the infinity of the universe in the gurgling waves of water, thus establishing another connection between the inner world and the outer world in experiencing the rhythm of nature.

As time goes by, the fishing village still has small boats, and the scene is still the fisherman returning home at sunset. Some artists no longer use the brush to reiterate the classical motif but to use the camera.

700 years later, the time has changed, but Chinese history and aesthetic values keep shaping the perception of the landscape. Michael Cherney, a New York-borned photographer. He traveled extensively through China, searching for monuments and historical sites related to Chinese art history, and through Cherney’s lens, viewers are able to capture the evolution of East Asian culture through the lens of the photographer, who was the first contemporary work of photography to enter the Asian collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This series of “Eight Views of Xiao Xiang” is a scenic spot in the Xiaoxiang River, which runs through Hunan Province. and was described in “Dream Pool Essays” of the Song Dynasty. It is a subject of landscape paintings for generations of artists. Michael’s “Eight Views of Xiao Xiang” series follow a geographic sequence, starting with the southern district in the upstream reaches and continuing to the northern wetlands in the downstream; each work is marked with the specific geographic coordinates of the place where the photographs were taken. At the same time, the title of each scroll corresponds to the title from the “Eight Views of Xiao Xiang” poems and paintings from ancient times.

Fishing Village in Evening Glow is the last piece from the series. This photograph was taken on the banks of the Yuan River, which corresponds to the fishing villages depicted in ancient paintings and poems; the Peach Blossom Spring of the Peach Blossom Source also flows into the Yuan River at this exact point. Unlike the depictions in ancient art and academic works, in this work, the excavator unloads the sand collected from the riverbed, and the conveyor belt of the machine extends our view beyond the frame.

These two works both evoke the theme of fisherman, and the photographic design of the frame is similar to that of Wu Zhen’s paintings from the Yuan Dynasty. Both have a poetic open space where the viewer’s eyes can be subtly stretched out and contemplated.The difference is that the fishermen’s village in Michael’s photographs is clearly not a visual reproduction of the historical idea of seclusion, and the two works ultimately have very different intentions; in Michael’s shots he reflects the environment of the Xiaoxiang River basin and the changes in the local mythological style of life, in contrast to the ancient theme of “Fishing Village in Evening Glow”. For him, creation is not only a retracing of the past, but also a reverence for nature, and a remembrance of the harmony between human and nature. Michael once said, “When I look at a place that holds a great deal of history and cultural memory, I use photography to capture a moment of its existence, which is fleeting but real.”

The illusion of ``landscape`` between variation of reality and fiction

Yau Wing Fung, Floating Mountain VI, Ink and color on paper, 27 x 54.7 inches, 2019

This period of historical transition was marked by more complex social, political, and economic changes. In 1644, when the central region was once again under foreign domination, the artists of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties embodied the tendency of the conservative anti-orthodox school of painting, and their works were innovative and highly self-expressive. Bada Shanren (1626-circa 1705), one of the four monks of the Qing Dynasty, was the ninth-generation grandson of Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang. The fall of the Ming dynasty brought a fatal shock and trauma to the perception of the world of Bada Shanren, who was then a member of the Ming royal family. The patriotic emotions of grief and anger over the loss of their family and country could not change the reality of the overthrow of the Ming dynasty. At that time, Bada Shanren’s life was at stake. To escape the persecution of the Qing regime, he became a monk and went into hiding, pretending to be crazy and mute.

As a result, Bada Shanren blocked the connection between himself and the outside world, internalizing his inner frustration and strong anger in the practice of ink art, and creating an artistic expression that was contrary to the orthodox conservative school of painting and highly personal, which had a profound impact on later generations of Chinese art.

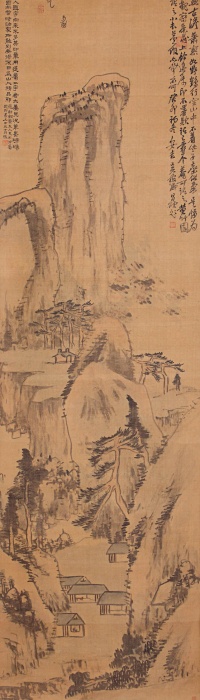

Bada Shanren, Gutan Xiaoliao, 180.3 cm x 49 cm,1864,Collected by Wang Fangyu

Gutan Xiaoliao is a work composed by Bada Shanren in his later years. The mountains are painted horizontally and vertically with strong, bold strokes, from the bottom through the platform as a bending path to the clouds. Although the brushwork of Dong Qichang is used to paint the landscape, there is no sense of elegance and calmness; although the eaves are strewn between the pine forest and the quartz, there is no room for them, and they are cold and desolate.

Throughout the painting, the mountain peaks stand tall, giving the viewer a strong sense of oppression. When the viewer finally reaches the top of the peaks, they are inscribed in the odd characters created by Bada Shanren, whose poetry, signature, and name are so difficult that scholars of the last century have learned their meaning only through extensive research.

The character on the upper left side is “ge xiang ru chi”, and “Ge” refers to Bada Shanren himself, while “Xiangru” refers to Sima Xiangru, who according to the history had the stammer. Bada Shanren means that he is also a stammer as Simai Xiangru. On the right side is the date of March 19, 1644, when the Ming Emperor Chongzhen hanged himself.

Unlike the ancient landscape that were based on the four hermit images of “fishermen, woodcutters, cultivators, and literati”, these symbolic images of hermits do not appear in his paintings. However, the characteristic of cryptograms still permeates in Bada Shanren’s works. The work is inscribed on the upper right by the modern master Wu Changshuo (1844-1927) and on the upper left by Lu Cuo (1851-1920), who wrote that the work had been collected by Yan Xinhou (1838-1907), a child of the Qing painter Yan Heng (Yan Rongzhai). Only those who can understand his mind can see his inner world across time and space.

Unlike most ink painters, Bada Shanren did not paint any landscape works until his later years, which is rare for an ink master. We think he probably did not reconcile with himself until late in his life. He began to create robust and minimal landscape paintings. The oppressive rising visual impact, the desolate gullies, the empty distant horizons, and the final closing stroke in the sky on March 19 are the cryptic words that Bada Shanren has left behind for future generations: the land in his heart is the home country that he can never return.

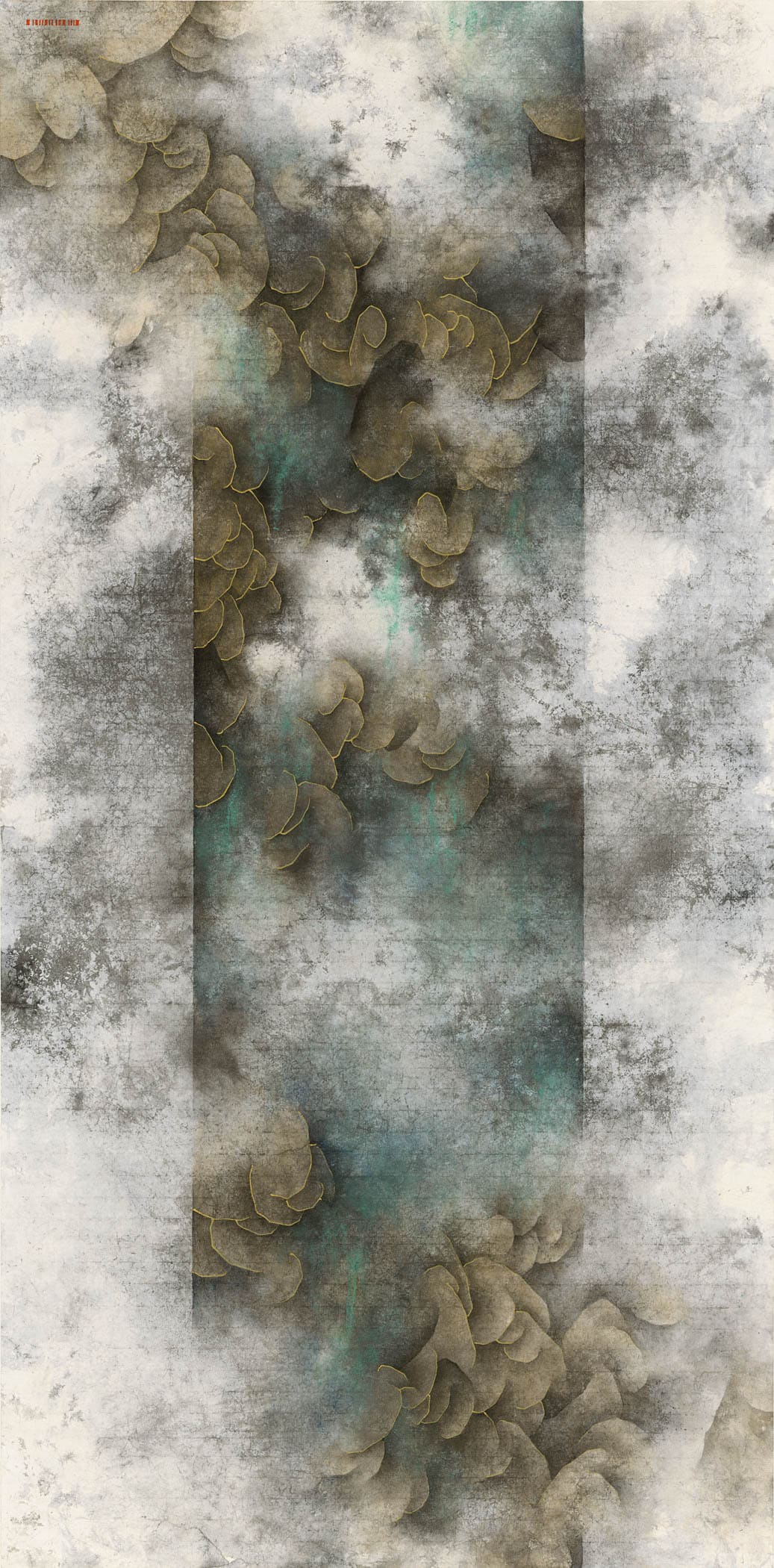

From Bada Shanren to Yau Wing Fung, the historical contexts have changed, and the real and imaginary approaches are similar, forming a subtle interplay in the understanding and expression of the ” reclusion ” concept.

In China at the beginning of the second century, the dramatic changes brought about by technological development profoundly changed the way people perceived landscape. The need for natural landscape and the longing for seclusion were the same, but the concept and approach had changed fundamentally.

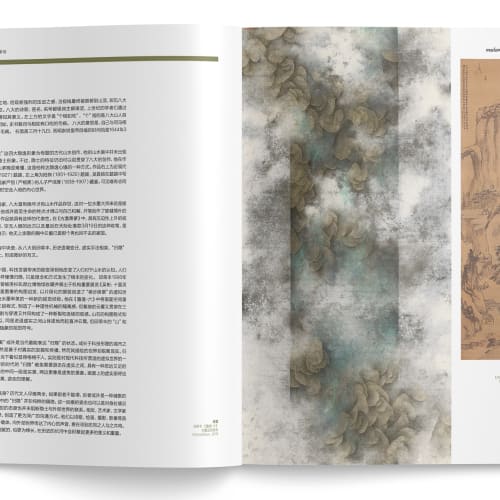

Yau Wing Fung was born in 1990 in Hong Kong. His work was collected by the LACMA and exhibited in the major exhibition – Wu Bin: Ten Views of a Lingbi Stone. Inspired by the composition of satellite images, he creates a virtual world of “moving scenes” with segmented landscapes, constructing a new visual experience based on the traditional ink and wash aesthetic. In “Floating Mountains – VI”, he vertically divides the space into three equal segments, creating a sense of rational and mechanical isolation, but the wispy clouds and mist run through all three segments, creating a sense of fracture and continuity. The composition of the Mountain is similar to that of the previous work by Bada Shanren, in that the mountain rises from the ground to the clouds in the same manner, but Yau’s “mountain” and “water” are transformed into extremely abstract visual symbols.

For Yau, “detachment” is perhaps the most contemporary expression of “reclusion”. The city is shaped by technology, which is based on the discovery and dissemination of reality, but the world it depicts is detached from reality. The reclusion of the center and the withdrawal from reality may seem out of place at the moment, but it is actually a response to the virtual world created by modern technology. In the age of information explosion, “reclusion” inevitably requires a kind of distant and close guarding between the real and the imaginary. The middle section of “Floating Mountains – VI” is a focus scene, while the two sides are more like a defocused scene. The reality and the fiction on the screen echo the artist’s understanding of reality and fiction, abstraction and wandering.

Yau Wing Fung, Riding Mist VI, Ink and color on paper, 70.4 x 37.8 inches, 2019

To make contributions to the world or to live a secluded life? This is a paradox question for generations of literati. If the former cannot be achieved, the latter may be a kind of silent rebellion. The “reclusion” in Chinese artistic imagery is not pure isolation; this retreating gesture can also be a kind of resistance to the situation in which one finds oneself. This transcendent attitude does not block the connection between the hermit and the outside world. On the contrary, by returning to their innocence and nature, artists and writers have created a deeper form of communication. By using poetry, painting, photography, video and other media with the characteristics of each era, they conveyed the voice of their hearts to the outside world and found the similar-minded people to share their feelings with. This kind of cherishing is euphemistic and delicate, and also more long-lasting, and will accumulate more meaning in the long history.