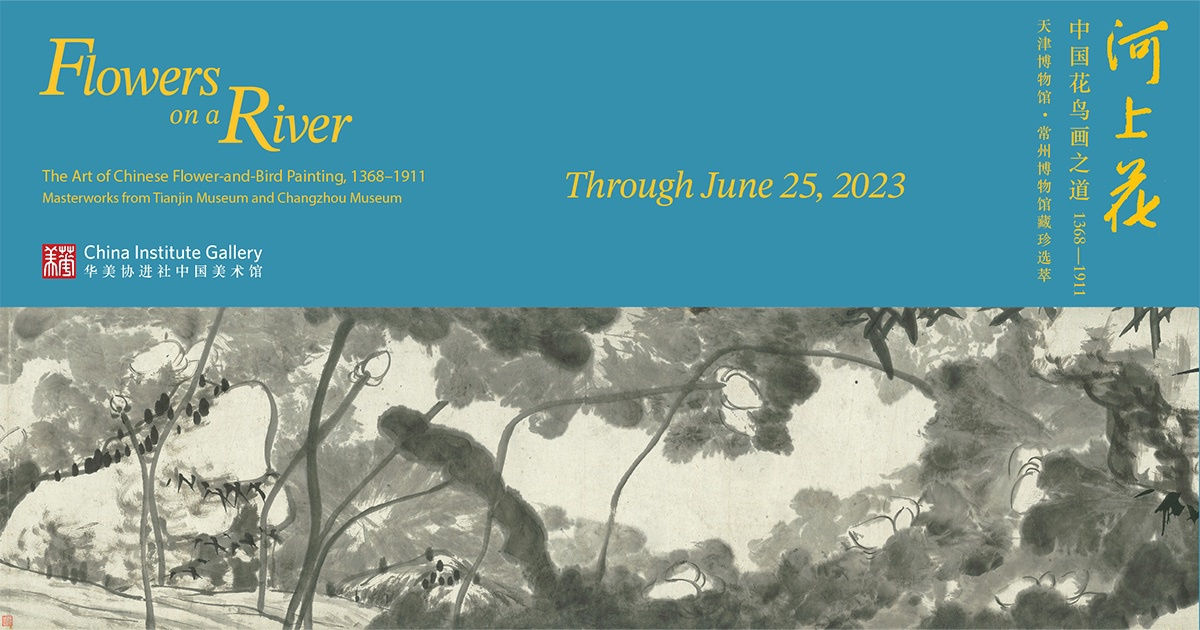

Holland Cotter, Chief art critic of The New York Times and winner of Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, once wrote of the China Institute Gallery as an institution that “consistently produces some of the best Asian shows in town, with first rate material, handsome installations, and catalogues by some of the more glamorous specialists in the field.” His words provide an apt description of China Institute Gallery’s current exhibition Flowers on a River: The Art of Chinese Flower-and-Bird Painting, 1368-1911. The show comprises more than a hundred exquisite examples of Chinese old-master paintings, borrowed from the exceptional collections of Tianjin Museum and Changzhou Museum, some of which rarely travel outside China. In conjunction with the exhibition, China Institute has also produced a comprehensive catalogue with essays by acclaimed scholars, providing extensive art historical context and in-depth analyses of the work shown.

Exhibition Installation

Among the cherished masterpieces in the exhibition, none surpasses the prestige of a monumental scroll over 42-foot long by the 17th-century monk artist Zhu Da (1625-1705), also known as Bada Shanren. A descendant of the fallen Ming royal family, Bada Shanren lived a life of concealment. The complex emotions that he had felt in the face of Manchu takeover in 1644 and the subsequent establishment of the Qing dynasty, but could not communicate openly, found wonderful expression in his art. Ink painting, calligraphy, seals, and poems mark the four “mediums” of his practice. Thanks to scholarships done by art historians like Wang Fangyu, Richard Barnhart, and Lee Hui-shu, we are able to know more about the life and work of Bada Shanren.

When describing the long handscroll by Bada Shanren now on view at the China Institute Gallery, Lee Hui-shu remarks, “No work of art better exemplifies the complexity and drama of Bada Shanren’s world than the Tianjin Museum’s Flowers on a River of 1697.” Here the flower refers specifically to lotus, a symbol of purity and a subject that held special meaning for Bada, as that of water lilies for Monet. Richard Barnhart wrote that “lotus holds within itself virtue, redemption, and rebirth in another realm;” its symbolic meaning echoes Bada’s artistic as well as spiritual disposition.

As we move along the scroll from right to left, the narrow format shows a thin strip of vista with rocks, bushes, water, and lotuses, which often extend beyond the edges in moments of intentional cropping. The painting’s viewpoint stays low to the ground, which allows one to look closely not only at the natural environment but also the brushwork and tonality with which the forms are masterfully rendered.

Exhibition Installation

The painting is followed by Bada Shanren’s inscription, written in a calligraphic style that is deliberately artless and forthright, distinctive to Bada Shanren. It records a puzzling free-verse ballad, with obscure historical references and opaque literary allusions, as ways of concealing his true sentiments. Close study reveals a complex web of emotions stemming from his identity as yimin, or remnant of the old dynasty, a concept that underpins much of his artistic practice. In Flowers on a River, the sorrow that is often found in Bada Shanren’s early work is supplanted by a sense of serenity and liberation, as he finds solace and redemption in landscape painting towards the end of his life.

Exhibition Installation

Besides the eponymous centerpiece of the exhibition Flowers on a River, the show is also jam-packed with gems from the 14th to 19th century, supplementing the theme “flower-and-bird paintings” with prime examples from both the court and literati traditions. The show provides a comprehensive overview of this genre. To borrow Holland Cotter’s remarks again, “For a walk-in experience of just how big small can be, look no further.”

Editor: Leo Yuan