C.C. Wang 王季迁(1907-2003) often said proficiency in Chinese calligraphy is a requisite for connoisseurship of and collecting Chinese literati paintings. He started his life preparing for a journey as a traditional literati painter and collector. In the U.S., he became one of the most important 20th century collectors and connoisseurs of classical Chinese literati paintings and earned his place as a modern 20th Chinese painter, calligrapher and a calligrapher of abstract art.

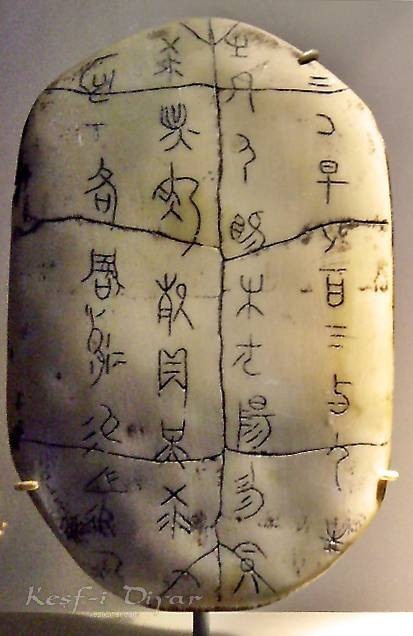

Jia Guwen 甲骨文, Baidu Encyclopedia

Chinese writing can be traced to inscriptions engraved on oracle bones, seen at 15th century B.C. This example demonstrates the criterion was already in place for the execution of elegant, powerful and refined Chinese calligraphy. Development of speaking and written language are necessary building blocks for a stable and civilized society. As Chinese writing evolved, Chinese ink, Mo, 墨, was invented, then invention of brush came next for keeping records. Chinese calligraphy is intricately intertwined with the development of Chinese civilization and its educational, legal and monetary system. The respect for and importance of scholarship can be traced to Consfuscian 孔子 (551 B.C.- 479 B.C.) teachings during the Spring and Autumn 春秋 (770 B.C.-4 76 B.C.) and Warring States战国 (476 B.C.- 221 B.C.). Records indicate beautiful calligraphy by Wang Xizhi 王羲之(303 A.D.- 361 A.D.) was treasured by collectors. Along with calligraphy, came painting. For this reason, Chinese literati paintings are inseparable from Chinese calligraphy. To examine a few historically important master painters’ works once in C.C.’s collection, paintings by: Dong Yuan 董源 ( 943 A.D.- 962 A.D.) Mi Youren 米友仁 (1074 A.D.- 1153 A.D.), Zhao Mengfu 赵孟頫 (1254 A.D.- 1322 A.D.), Ni Zan 倪瓒 (1301 A.D.- 1374 A.D.), the Four Monks, the Ming Masters, the Four Wangs; all these great painters and calligraphers, each, his paintings and calligraphies were all intricately connected and executed using zhongfeng bimo 中锋筆墨 (to be explained in the next paragraph). The traditional criterion was that if a literati scholar were to earn respect, he would execute either his calligraphy or painting in his characteristic bimo using zhongfeng bimo, expressing his visions of the abstract landscape in his own creation. This is also the reason that both calligraphic works and paintings of the same artist have been found in later eminent collections. Some people have remarked that Chinese literati only dealt with landscape paintings. Landscape paintings probably were favored by collectors. The number of extant early paintings of flowers, insects and plants is rather small, inspite of the fact that a larger number was known during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). High-quality Chinese portrait work seems to have disappeared by early 15thcentury, though some was done later under the guidance of Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), which showed foreign influence.

From extant Chinese paintings dating to the 10th century, the high standard set for bimo 筆墨 or translated as brush stroke in ink, is accomplished by acquiring a technique called zhongfeng 中锋 when writing with a brush, a very difficult feat. To be proficient in zhongfeng, the callgrapher must hold the brush upright and in the center, the tip of the brush has to be centered in the middle, consequently, as the calligrapher moves his brush, all his force, energy and power will be channeled directly from the top, through the brush, to the tip and then to the calligraphic line, full of vigor and force which can only be accomplished from years of practice.

For more than 2,000 years, China, in spite of her contacts with her neighboring countries, was a country very content living with its doors closed to the outside world. When China was mercilessly defeated during the Opium War in 1840 and then her subsequent signing of the Nanking Treaty in 1842, giving foreigners many special privileges, and eventually a court system set up by foreigners in China allowing foreign criminals who had commited crime in China to be judged not by Chinese laws, but foreign laws, it was a moment of rude awakening for the country. For a nation of subservient subjects accustomed to more than two thousand years of authoritarian leadership handed down through Imperial Edicts, this kind of humiliation aroused intellectuals and scholars to rebel against the subjugation by foreigners, the annexation of territories and wars when China was defeated without fail. A revolution began to forment with a desire to destroy the old system which was blamed for all the sufferings, social problems and the shame of being labeled the invaidation of East Asian, 东亚病夫. Many reformists began to question the value of the traditional Chinese educational system, emulate and worship the West. A groundswell movement grew to change the rigid, archaic set-up, which eventually reached the field of art. Some artists of the “New Wave” began to study and emulate works of Western art.

C.C. Wang was born into a traditional literati family in Suzhou (苏州) during this period of change. He loved to paint and was a born artist. His schooling during his youth was the traditional upbringing, which meant he had to study the classics and learn calligraphy which were the most basic requirements of a typical Chinese education for centuries. Practicing calligraphy from an early age was a daily routine for all students. Due to his love of literati paintings and wish to be a connoisseuer and collector, he became a mantee of two of the most prominent collectors, first, Gu Linshi, 顾麟士 (1865-1929), then Wu Hufan, 吴湖帆 (1894-1968), both were very successful and highly respected calligraphers, painters, connoisseurs and collectors from renowned families with several generations of tradition in connoisseurship and collecting.

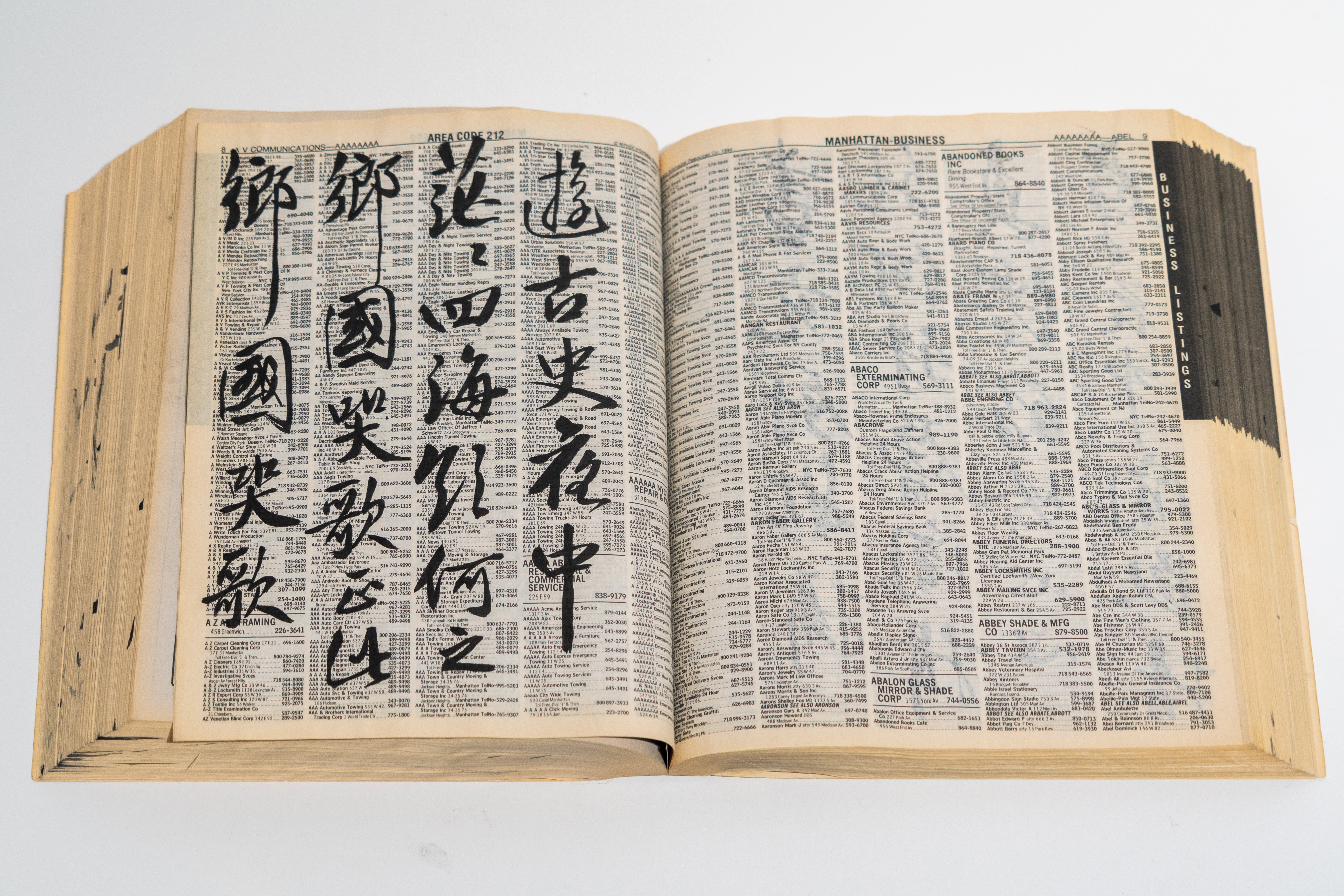

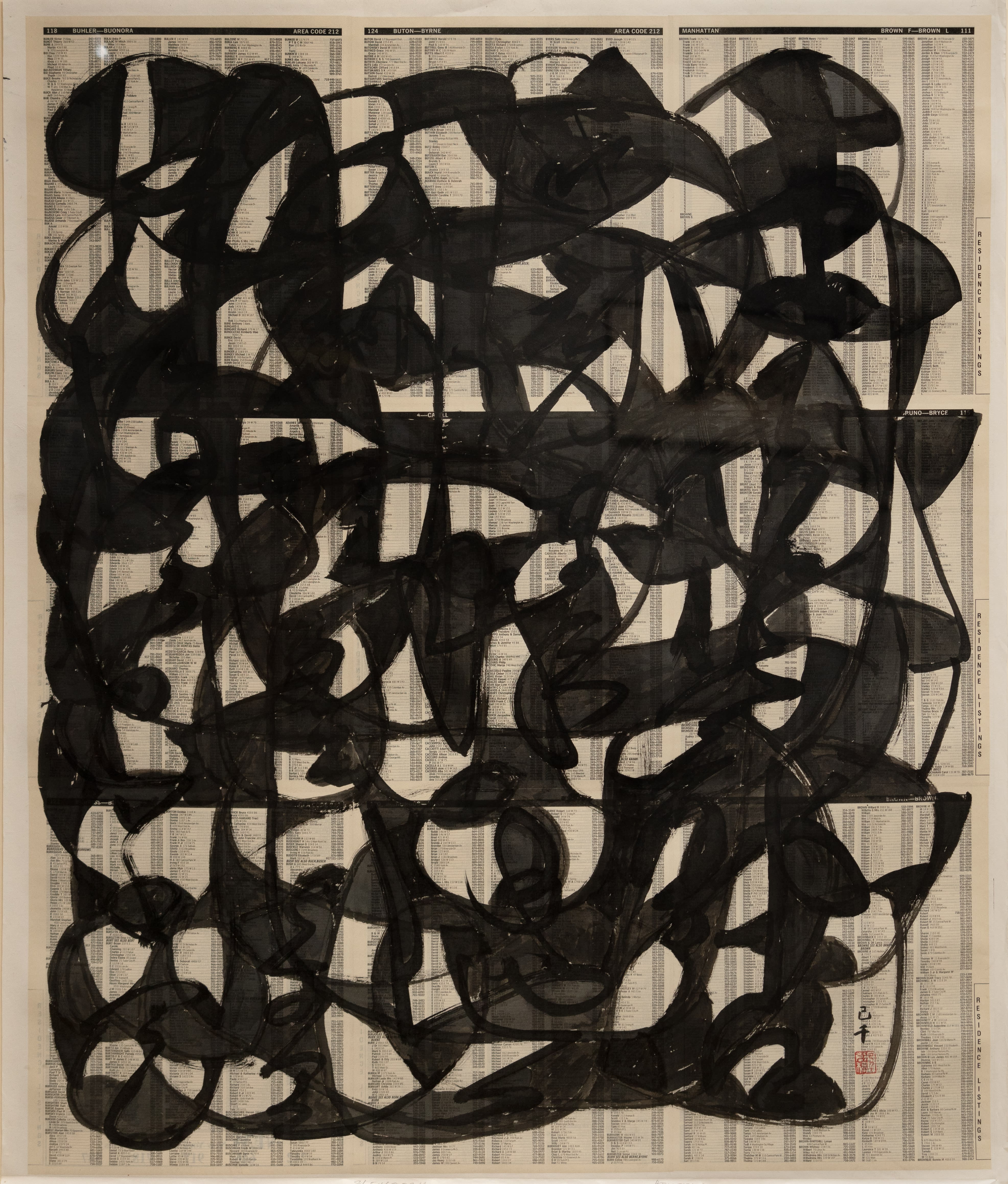

C.C. was Wu Hufan’s first student. Wu Dazhen, 吴大徵 (1835-1902), once a governor of Guangdong 廣東 and later Henan Province 河南, also a painter, calligrapher and highly respected collector, adored his only grandson, Wu Hufan, a child prodigy, who impressed his grandfather with his preconscious way of absorbing the teachings of classics, calligraphy and paintings with lightning speed at an early age. Wu made sure his grandson was well taught by the most respected tutors, collectors and painters at the time. Wu Hufan, a well-born gentleman of the old world with an illustrious collection, made an exception in accepting C.C. as his first student, the impetus was C.C.’s bimo and gifted eye of a connoisseur at an early age. C.C. had great respect for his two mentors, followed their footsteps of constant practice of calligraphy and emualting bimo of great masters available in each respective collection. This habit continued to his later life, when he would practice his calligraphy on pages of New York City White Page telephone books, using the zhongfeng technique, as seen in Example 2. Some people commented that he was too frugal. The truth is that in his Shanghai days, many people practiced calligraphy on daily newspapers.

|

|

| Example 2. Private collection |

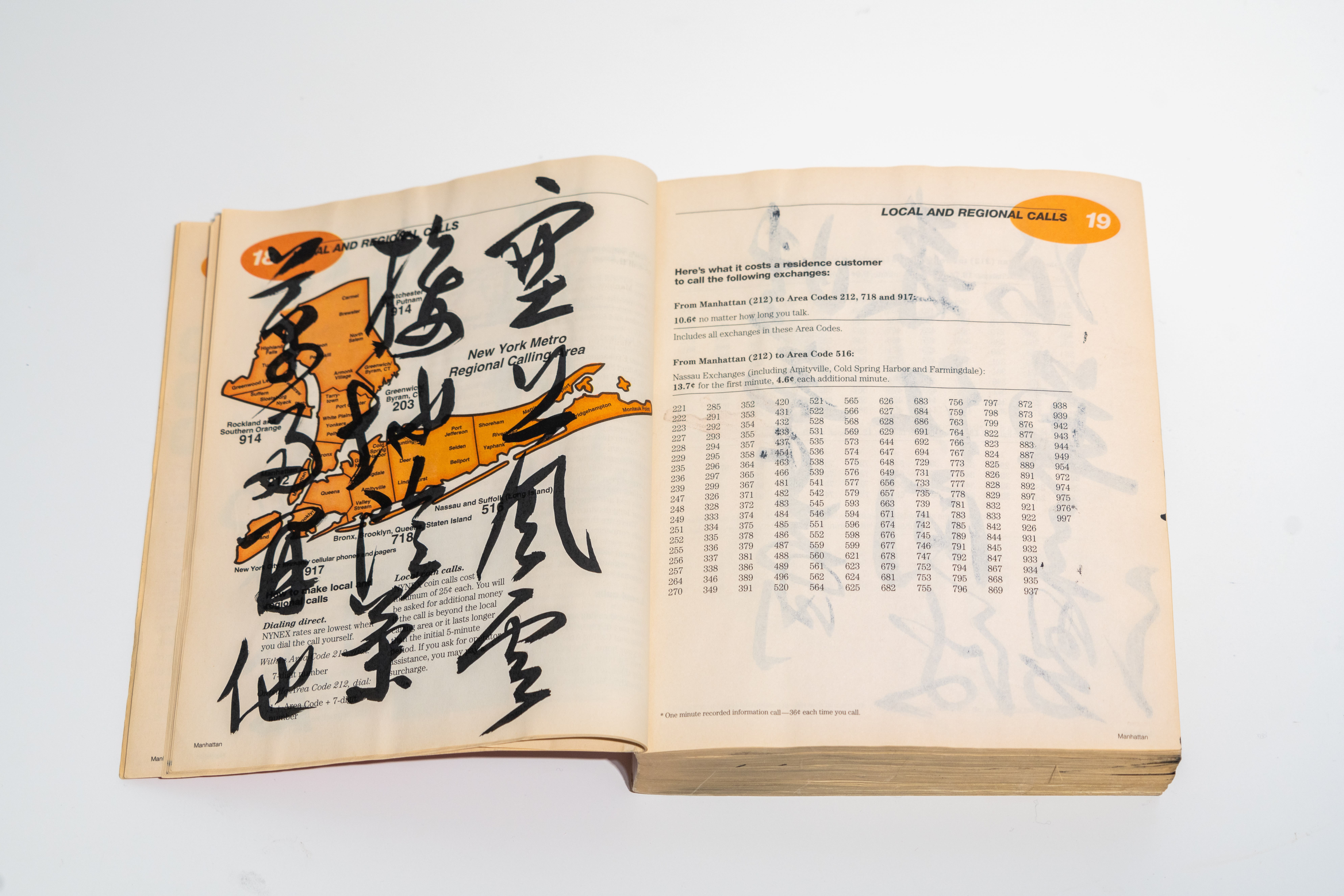

He took great pride in his calligraphic work and would say his bimo was authentic and first-rate zhongfeng. In the four decades I had known C.C., he never boasted to me of the quality of his fabulous collection, but once said with great pride that he had been asked to write a calligraphic work in honor of Deng Xiaoping’s birthday 邓小平. I was naïve enough to ask the reason for this request, he replied that his bimo was peerless. He also took great pleasure emulating the different types of bimo of basic components of landscape paintings of great masters in his collection, in zhongfeng bimo, as seen in example 3, which shows how tree branches are rendered in literati paintings. His inscription says 亁筆中锋, which means dry brush zhongfeng.

Example 3. Private collection

C. C., early in his life, painted in the traditional literati classical style. While he was in Shanghai, he was exposed to Western paintings in International Concession territory, and impressed particularly by the Western post-impressionist works. Under the advice of Liu Haisu 刘海粟 (1896-1994), he decided to come to the U.S. to study Modern Western paintings in 1948. 1949 was the momentous year when a revolution changed the country to a communist regime. C.C. stayed in the U.S. with his family. While he had to make a living, he was relentless in following the teachings and examples set by his mentors, i.e., the practice of calligraphy and emulating bimo of great masters in his collection. For centuries, literati painters emulated bimo of great masters in famous collections in order to learn and experience the characteristic bimo of the great masters. One of the few avenues for this kind of exposure was to have a respected collector as a mentor, whose collection would be available for one to get a chance to see and emulate bimo of a great master. There were neither museums nor universities. C.C. was fortunate to have an incredible collection for study. While he continued the discipline acquired from his mentors, he was constantly exposed to Western ideas, Western art, which he loved. His painting style began to change from the traditional literati style to something of his own creation showing Western art influence. He became a successful and highly respected painter in his own right.

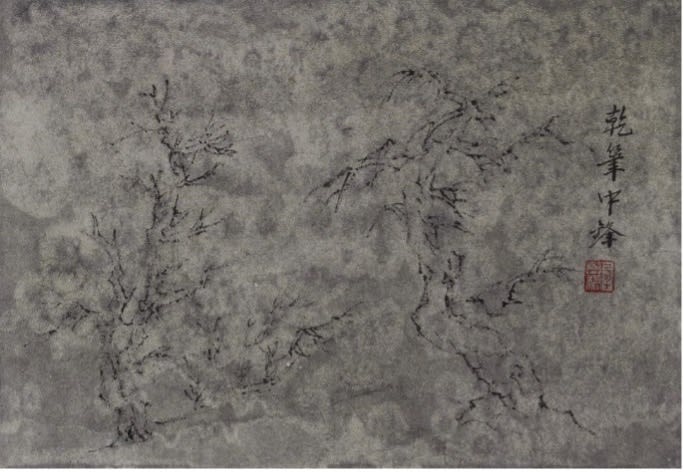

Good art transcends all boundaries. C.C. loved beautiful artworks from different cultures. He visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art often to study Western paintings, which he greatly admired. He also had a chance to meet and study the abstract works of Franz Klein and Bryce Marden. He said Klein and Marden’s abstract calligraphic works showed the influence of Chinese calligraphy. With his constant practice of calligraphy, he began to innovate. He said to me the abstract work executed in his late-life evolved from his daily practice of calligraphy. According to him, the uniqueness of his abstract work was related to the powerful bimo executed to produce the continuous line in his abstract work, using zhongfeng bimo filled with vigor and energy. He said his abstract calligraphy might appear to be a work of Western abstract, it is actually also very Chinese because all the lines are drawn using the zhongfeng bimo and good Chinese calligraphy is itself an abstract expression of the calligrapher.

Example 4, private collection

His abstract calligraphy developed in several directions, one of which is seen in example 4. He said this kind of abstraction evolved from his calligraphy. The design may be calligraphic in Chinese origin, but in its execution, the product embodies the influence of Picasso, Matisse, Van Gogh, Modigliani, Rousseau, and Magritte, whose works he greatly admired.

Example 5 is an example of C.C.’s innovative creation, a culmination of his many days of practice on New York City telephone books and his fascination with abstract calligraphic type of works by Franz Klein and Bryce Marden. He pasted together many sheets of telephone book pages, and created an abstract creation originating from Chinese calligraphy.

|

Example 5, private collection |

He was grateful for the opportunities afforded him in the U.S. as a refugee immigrant from China. He loved Chinese as well as Western art. Towards the end of his life, it was a moment of recognition, that he, C.C. Wang, who started his painting career as a Chinese traditional literati painter, had evolved as an artist of many talents with diversified venues to create works which were an amalgamation of the traditional skills paramount to the success of a Chinese literati painter and the great creativity and imagination seen in the field of Western Modern Art. This conglomeration which is a synthesis of the artistic aesthetics of the East and the West.

This reminds me of an anecdote that C.C. told me when he and Professor Wen Fong 闻方were talking about the 1997 sale of some of the masterpieces from his collection to Oscar Tang as Oscar’s promised gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. C.C. congratulated Wen Fong of Wen’s contribution in bringing the best of Chinese literati paintings to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, therefore to the U.S. a permanent collection of some of the most important National Treasures in the history of China, the irreplaceable, rare and largest number amassed outside of China. For centuries, these paintings had been locked up either in the Imperial Collection or private collections, an elitist art not seen by most people. Due to the two revolutions in China, first in 1911 and later in 1949, these collections were dispersed, and some of the most important treasures ended up in the U.S. It is American philanthropists’ generosity, spirit of adventure and Wen Fong’s genius, diplomatic skills and foresight to make this possible. It is a rare historical opportunity which probably will not be repeated for years to come. He said Wen would occupy an important place in the history of Chinese art for his accomplishments. Wen countered by saying that C.C. Wang will be remembered in history not only as one of the most important collectors, connoisseurs of the 20th century, but be looked upon as an eminent painter and calligrapher, a feat of historical importance.