The life and art of C. C. Wang (1907-2003) have been chronicled and analyzed in numerous books, articles, and at least one doctoral dissertation.[1] His reputation as a collector, connoisseur, and painter is legendary in the world of Chinese art. One aspect of his work that has received less attention is his contribution to the art of Chinese calligraphy.

Fu Qiumeng Fine Art has assembled an extraordinary group of late works that help us to expand and update our understanding of the creative energy of the master during the last years of his life. Carefully culled from the collections of a small group of C.C.’s friends and students in New York, “Rhythms of New York: the Calligraphy of C. C. Wang” reveals a late burst of creativity that is simultaneously intimate and intense. Like New York City itself, Wang’s late calligraphic works are imbued with a special vitality and energy, a unique blend of a multitude of influences—old and new, East and West, elite and popular—a toughness and swagger that epitomizes the “city that never sleeps!”

C.C.Wang, Huangshan, 1987 ©Arnold Chang

C. C. Wang was born in 1907 in Suzhou, a city known for its beautiful gardens and a long tradition of art and culture. He emigrated to the United States in 1949, and, aside from a few years spent teaching in Hong Kong, he made New York his home until his death in 2003. Having lived more than half of his life in New York, C. C. absorbed all that the city had to offer and was both a witness and contributor to the world’s most dynamic metropolis during a transformative period in its history.

Wu Hufan

Wu Hufan

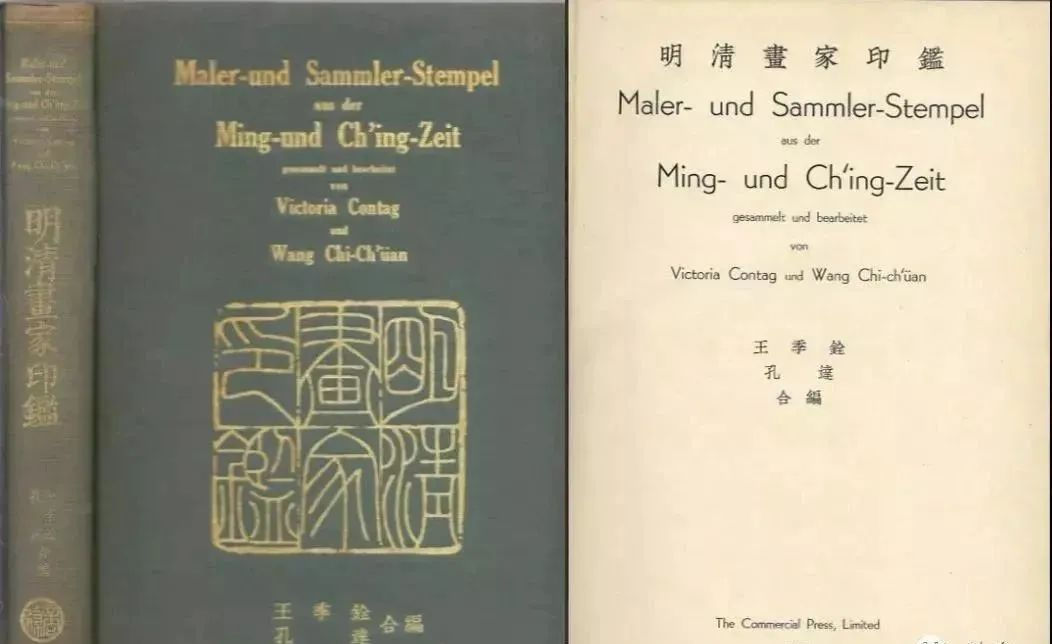

C. C. Wang, came from a privileged background in China. He studied painting with the renowned masters Gu Linshi (1865-1929) and Wu Hufan (1894-1968). He served on the executive committee for the famous International Exhibition of Chinese Art, held in London in 1936, and, along with the German scholar Victoria Contag (1946-1972), published an important compendium of Seals of Chinese Painters and Collectors of the Ming and Ch’ing Periods.[2]Yet, when Wang arrived in New York, he found that there was very little appreciation for Chinese painting and virtually no expertise in the U.S., even among museum professionals. He knew it would be impossible to make a living just by selling his own traditional landscapes, which were conservative even by Chinese standards of the time. Initially he used his artistic skills to find a job designing wall paper and painting decorations on lamps, but a career in commercial art would never satisfy his deeper artistic ambitions. Blessed with good business sense, a law degree from Suzhou Law School (based in Shanghai), and proficiency in the English language, C. C. had many more pathways to success, or at least survival, than the average Chinese artist, and he was able to gradually generate income through a combination of real estate dealings, advising collectors, authenticating Chinese paintings for institutions and dealers, teaching painting, and the occasional sale of his own work.

Seals of Chinese Painters and Collectors of the Ming and Ch’ing Periods.

His love for Chinese painting in particular, and art in general, sustained him and inspired him. On the one hand, he generously shared his experience and expertise with curators, professors, dealers, collectors, and students. It is no exaggeration to claim that C. C. Wang was instrumental in helping to educate at least one full generation of scholars about the traditional Chinese approach to Chinese painting practice and connoisseurship.

On the other hand, living in New York allowed Wang to broaden his artistic experience by offering, through museums and galleries, unsurpassed exposure to the art of virtually all cultures and periods. Although C. C. never attempted to study European and American art in a systematic way, even while still in China he was not unaware of developments western art, which he discussed with artist friends such as Liu Haisu (1896-1994) in Shanghai. He also studied briefly with Zhang Chongren (張充仁) (1907-1998)[3], a Chinese western-style artist who had attended the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Upon his arrival in New York, Wang took a number of classes at the Art Students League, where he practiced life drawing and gained familiarity with a variety of media. His intent never was to become a “western” or “international” artist; his approach was that of a Chinese painter expanding his vision and broadening his overall understanding of art. In my conversations with him, Master Wang couldn’t remember the names of any of his instructors or classmates, but he did benefit from his experience at the Art Students League, and more importantly, from life in New York. Wang was very much aware of his predicament as a Chinese painter living and working in a foreign land and he made a conscious effort to find a way to bridge the two cultures:

“When I first came to the United States, I continued to paint in the Chinese traditional way because I realized if I gave up my own tradition to do something like the Americans did it wouldn’t mean to much to me. I wouldn’t feel too happy. But I went to see exhibitions of contemporary Western painters and I learned a great deal. Of course, I already knew Chinese painting—what was good and what was bad. I came to realize that holding on too long to a tradition for its own sake is never a good thing. And since I came here, I have opened my mind and I can see that. The Chinese idea of landscape for instance, in the traditional manner, is a little too narrow for this time. So I tried to pick out what I considered the good parts of Western painting and of Chinese painting in order to create something which expresses my own ideas and feelings. This, I think, corresponds to the ideas or intentions of modern painting.”[4]

Years later he explained to me:

“I knew of Pollock, Kline, Motherwell, and Tobey. I saw what they were doing, but I didn’t really understand it at the time. The first two important things I learned about Western painting are that it is meant to be seen from a distance, so composition is crucial, and that the ‘touch’ of an oil painter is similar to our brushwork, but not exactly the same because of the nature of the materials. Chinese brush and ink are much more responsive than oils and canvas, and brushwork is the one aspect that Chinese painters have explored in much greater depth than their Western counterparts.”[5]

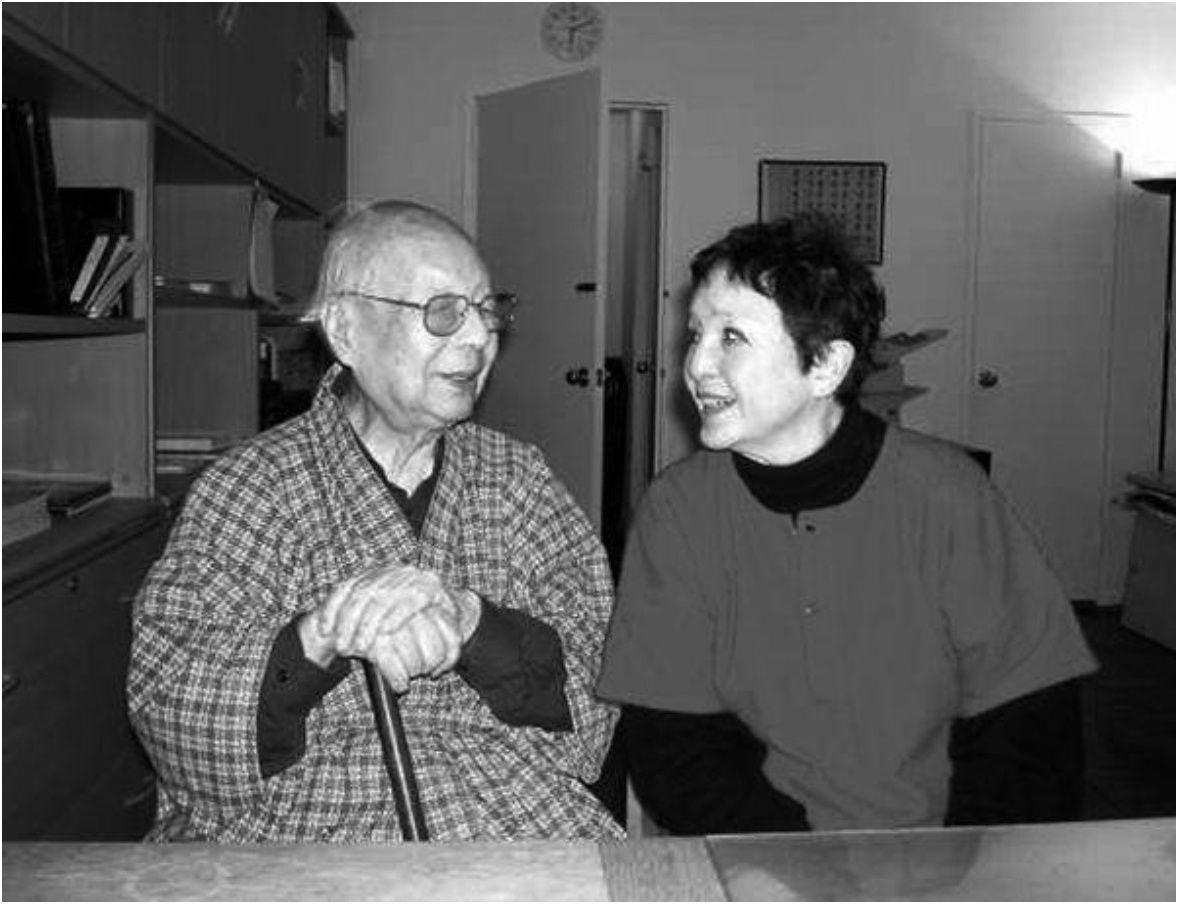

Arnold Chang, C.C.Wang, James Cahill, Kaikodo, NY, 1997©Arnold Chang

James Cahill, one of the leading scholars of Chinese painting in America and an old friend of C. C. Wang, remarked in an interview with Ming Hua, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Wang:

“If he had stayed in China, he would not have been called up by others . . . There was that tradition of continuing the great orthodox tradition among collectors and painters in China. C. C. had to break from that tradition in order to really develop. If he had gone on painting like Wu Hufan, in the orthodox tradition, it would be nothing. Xu Bangda went on painting and his painting is not very interesting because it is still orthodox standard Chinese landscapes. C. C. Wang developed something much more interesting by coming to New York.”[6]

Responding to Ming Hua’s query about the influence of western abstraction upon Wang’s work, Cahill continues:

“Of course yes. That was happening outside of China all over. There was a time that every young Chinese painter would see Abstract Expressionism and look back and say, ‘Wow, that’s like Chinese tradition. All I have to do is to take a big brush and go huhuhuhu and they would admire me as an abstracter.’ I cannot remember their names but young guys would try to do this and take it seriously. They are still around. They think they can sort of pick up the brush and ink, and do whatever and say that it is combination of Wu Daozi and Pollock. No, it is not. It is fake.

C. C. Wang was better than that. C. C. Wang, Chen Qikuan, and others were creating a kind of Chinese equivalent for what was happening in Western art. They were not imitating it. They realized they had to do something like it, to be taken seriously, and to make a next step as painters. They created styles depending heavily on chance formations. Chen Qikuan used to scatter the ink and color and then make a picture out of it. C. C. did that sometimes too. He would impress the paper with things, scatter ink with crumbled paper, and then make landscape out of it.”[7]

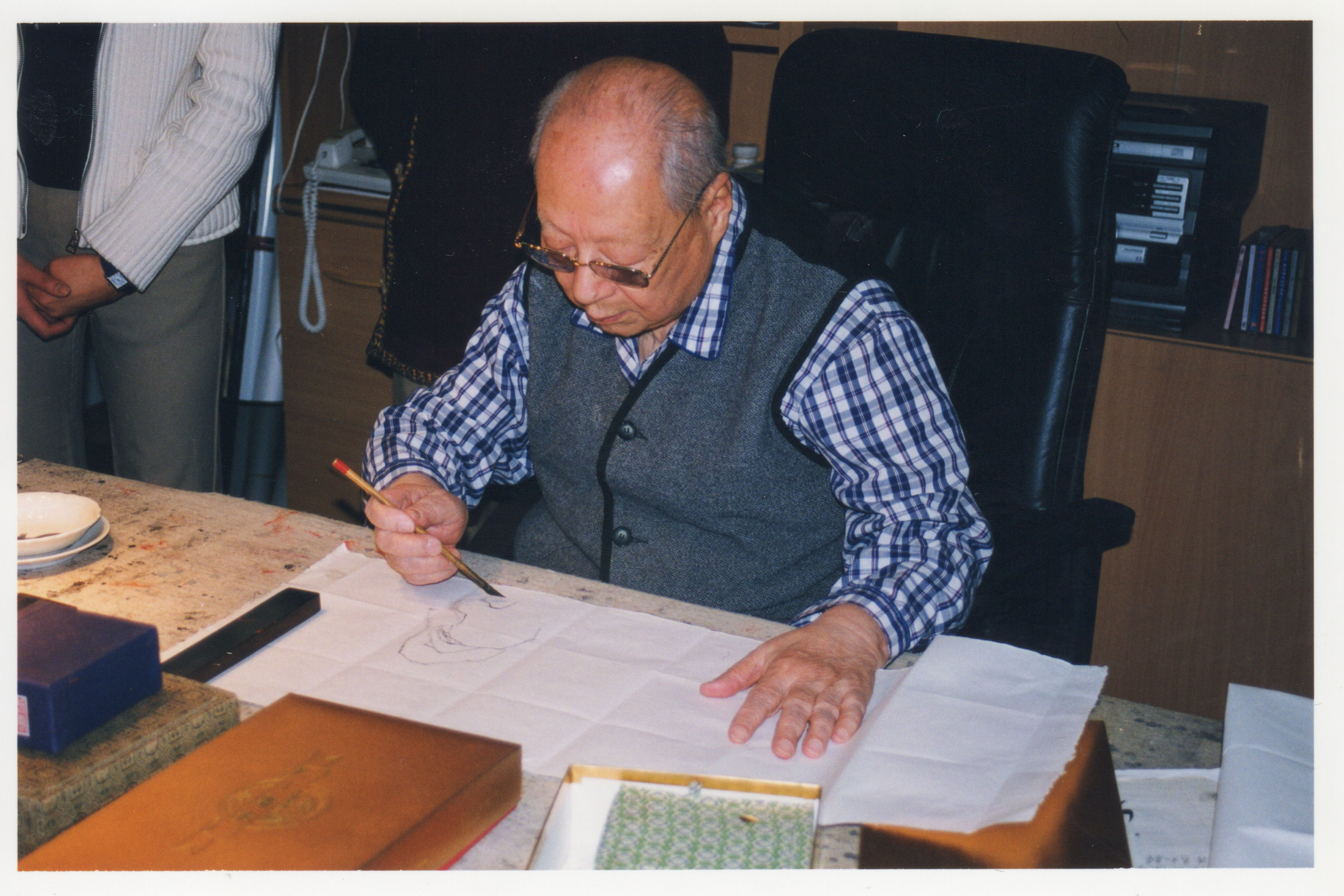

C.C.Wang, 2000 ©Arnold Chang

Over the next few decades, C. C. Wang developed his own personal style of landscape painting, which was thoroughly grounded in traditional literati aesthetics, but incorporated innovative techniques, including dipping different types of crumpled paper into ink and imprinting the random ink patterns onto another sheet of paper, to which he added brushstrokes and washes to build up mountain forms. He also employed a wider range of colors, and paid more attention to compositional structure than he had in his earlier works. The landscapes he painted while in China had emphasized a type of brushwork that was so subtle and refined that it was largely incomprehensible to the uninitiated, which meant it was virtually unintelligible to an American audience. Wang’s “breakthrough” works of the 1960s and 1970s were quite well received and were featured in a number of exhibitions in prominent institutions, yet much to his chagrin, his personal artistic achievements seemed always to be overshadowed by his prominence as a collector and connoisseur of ancient masterpieces—a trend that continues even today.

It was Professor Cahill who introduced me to C. C. Wang in 1977 when I was a student at U. C. Berkeley. Wang was in the Bay Area for the summer and was teaching two classes at the Chinese Culture Center in San Francisco. I enthusiastically enrolled in the classes, and I was so overwhelmed by C. C.’s depth of understanding and willingness to share his knowledge that at the conclusion of the two-month sessions I decided to forego entering the PhD Art History program at Berkeley and instead made up my mind to return to New York City to study full time with C. C. Wang! For the next twenty-five years, until his death in 2003, I benefitted from his generosity and mentorship.

Anold Chang and C.C.Wang,painting in Huangshan, 1987 ©Arnold Chang

C. C. recognized that I was a serious student who wanted to learn to paint in order to gain a deeper understanding of classical Chinese painting, rather than attempting to become a famous artist. He insisted that I learn painting the old-fashioned way, by copying the works of the old masters. It was my great fortune that he possessed the finest collection of paintings by Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing masters outside of China, and he allowed me to study and copy the originals! Throughout the decade of the 1980s I diligently copied handscrolls, album leaves, and hanging scrolls, mostly by Ming and Qing masters. I was fortunate to find a job at Sotheby’s (then Sotheby Parke-Bernet) cataloguing Chinese paintings for the auction house. As fate would have it, C. C. Wang was already a consultant there, so we spent the next decade and a half looking at paintings together and gradually building up an international market for Chinese paintings and calligraphy!

Brushwork (bimo 筆墨) was always at the very core of C. C. Wang’s artistic philosophy, but his conception of brushwork went far beyond a simple description of drawing ink lines on a page with a brush, it encompassed to an entire aesthetic universe, and the way he defined brushwork broadened as his own understanding of art deepened and expanded. In attempting to illustrate the nuances of brushwork Wang always compared the personal characteristics of an individual artist’s brushwork with the unique “voice” of an opera singer, citing Caruso as an example for westerners, and Meilan Fang for Chinese audiences, but he gradually supplemented this simple analogy with allusions to a more modern approach to music, jazz.

“Song brushwork [which is adjusted to compositional or descriptive ends] is like opera singing. Yuan brushwork [which is far more abstract] is like jazz. When you come to jazz, you can’t accept it at the beginning. Opera has more skill but jazz has more naiveté. Naiveté has to be original. Now my painting has become just like jazz music.”[8]

“In jazz music, you don’t have to know what the singer is singing about. Good brushwork is so beautiful it can make you look at it many times, like a good voice. When you hear singing, do you expect the singing to have a good story? It doesn’t have to.”[9]

The idea that C. C. Wang, perhaps the late 20th century’s greatest proponent of orthodox literati aesthetics was comparing Yuan dynasty painting to jazz, a quintessentially African-American invention, is remarkable!

I had many opportunities to watch C. C. paint. By the time I began studying with him, his experiments with the “crinkled paper” “texturalization” techniques had, to a large extent, run their course. He employed them more sparingly, and with greater control. His brushwork had matured with age and his mastery of the innovative techniques had strengthened his sense of composition. For someone like me, who was trying to learn to paint in the traditional manner, it was an absolute thrill to watch the master at work! At the time I naturally concentrated primarily on his more classical landscape imagery, but I was aware that by the middle of the 1980s he was also doing a variety of experimental works and beginning to focus more seriously on his own calligraphy. Other students were quicker to recognize the distinctive appeal of our teacher’s renewed involvement in calligraphy and his subsequent move towards pure abstraction. Some of my classmates had a specific interest in learning calligraphy, while others wanted to learn to paint but were not as burdened by “tradition” as I was at the time, as I stubbornly defended literati standards of quality (as if they needed to be defended!).

Arnold Chang, C.C.Wang, Zhu Qizhan, Forest Hills, NY, 1986 ©Arnold Chang

As a young child, C. C. Wang received a traditional Chinese education, which invariably included reading classical literature and poetry and learning to write calligraphy. He began writing characters at around the age of four or five, first learning from his father and later from a tutor. He practiced for an hour or two every day, gradually memorizing the content of the texts he was copying and simultaneously internalizing the brush movements required to duplicate the forms of the original models. Somewhere around 1980 Wang restarted a daily ritual of practicing calligraphy, something he hadn’t done consistently since he was a child. He continued this practice into the decade of the 1990s, and he began working with unconventional materials and developing fresh, new styles of “writing” that were sometimes devoid of legible content. By decade’s end it was clear to everyone who had been closely following his artistic career that his recent work represented yet another transformative phase.

James Cahill wrote an essay entitled “A Late Period for C. C. Wang,” in conjunction with “Living Masters: Recent Paintings by C. C. Wang, an exhibition at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.[10] Jerome Silbergeld updated his commentary to include a discussion of this exciting new chapter in the master’s career.[11]

C.C.Wang and Joan Stanley-Baker

Joan Stanley-Baker, known to C. C. as Hsu Hsiao-hu (Xu Xiaohu), wrote passionately about the freedom that the artist unleashed by rededicating himself to the age-old discipline of practicing calligraphy:

“Indeed, the exercise was stunning. The artist had broken through the sixteen-hundred year constraint that had kept Chinese artists from allowing themselves to stretch fully their imagination muscles and to experience fully the exhilaration of creativity within the discipline of calligraphy. This C. C. Wang now found himself able to do. Of course, it was not a sudden revelation, as if he had fallen into a hole, or out of earth’s gravitational sphere. But it is that when he finally broke through the last layers of constraints he found himself suddenly free. That freedom was sudden. But the result of eight decades of continuous work and thoughtful, wakeful work with his favorite instrument: the Chinese brush.”[12]

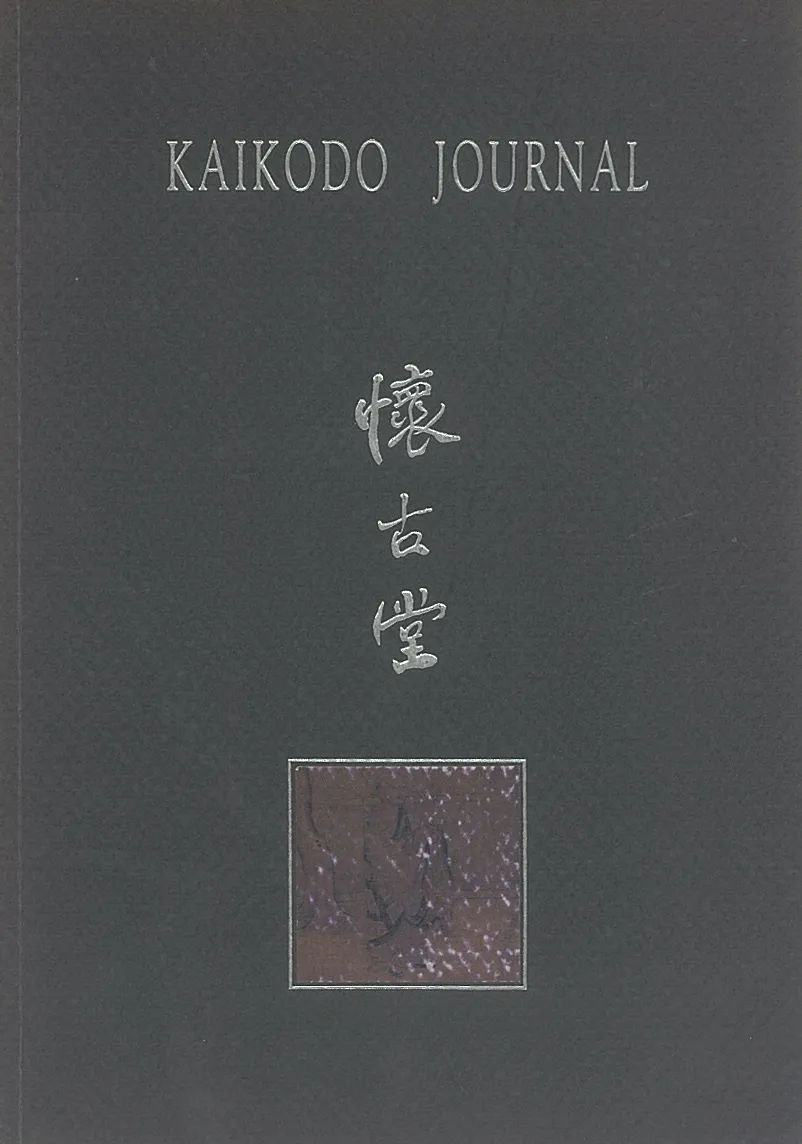

Howard and Mary Ann Rogers enthusiastically agreed to mount a retrospective exhibition at Kaikodo, their gallery on East 64th Street in New York (where I was employed at the time after leaving Sotheby’s), in celebration of C. C. Wang’s 90th birthday in 1997. The show included a sampling of Wang’s works from the 1930s through the 1990s, as well as a number of Ming and Qing masterpieces on loan from his personal collection. Featured in this show, in addition to his landscapes, were a small number of still lifes, calligraphies, and abstract images dating from the 1990s. In my accompanying essay published in Kaikodo Journal I wrote:

Kaikodo Journal III "Visions of Man in Chinese Art"

“Wang’s calligraphy and ‘calligraphic images’ (works that combine elements of calligraphy, such as lines and dots, but do not form actual characters) of recent years bridge the gap between his still life paintings and pure abstraction. These works challenge the traditionalists and modernists alike. Are they writing or are they painting? Can they be calligraphy if they don’t say anything? Although the works invite these questions, they don’t require absolute answers. To C. C., Chinese calligraphy, even more than painting, is abstract already and he emphasizes certain elements of calligraphy as a means of personal expression, adding movement to his harmonies of line, color, shape, and composition.”[13]

C. C. Wang himself explained:

“I have painted landscapes all of my life because I love them. But I realize now that when you paint a landscape you are, to a greater or lesser extent, borrowing the beauty of the natural scene. People are responding to your painting, in part, because they are responding to the beauty inherent in the mountains, trees, and water that you are depicting. Of course, how you arrange those elements—your use of color, wash, line, and form—defines your personal expression and your art, and viewers are responding to that as well. But the natural beauty of the subject matter influences how they respond. Now I want to create beauty that is completely an individual expression and is not derived from the subject matter.”

“At the highest stage, at the deepest level, there is no difference between Chinese and Western painting. They will always have some superficial differences, and some cultural characteristics, perhaps dictated by choice of media, but essentially the personal expression is the same.”[14]

Although Wang continued writing calligraphy throughout his life, painting was always his primary focus. He was not known as a calligrapher. He was not a poet and he rarely wrote inscriptions or colophons for the classical works that he collected. The paintings that he created after leaving China almost never included lengthy calligraphic inscriptions, usually just a signature and perhaps a date. He even simplified the characters of his name to make them easier to sign on paintings. As a painter, he saw himself as heir to the great tradition of Chinese literati painting and he struggled mightily to make sure that his own paintings lived up to the high standards that he himself had set.

C.C.Wang (1907-2003), New York City White Pages Telephone Book,

Medium: ink and color on Telephone Book,

signed Wang Ji Qian 王己千 on the first page, dated Wuyin, bayue 戊寅八月 August 1998.

But with calligraphy, I feel, he was less burdened by tradition. So as not to waste paper, he began practicing his writing on the pages of New York telephone books. This was just practice; he needn’t be afraid of making a mistake. He was free to write as much or as little as he wanted. He could experiment with different styles and ways of forming the characters. He could doodle in the margins. I’m sure that C. C. was genuinely surprised when he learned that students and friends found these informal practice sheets to be charming and engaging works of contemporary art. I can’t say for certain that it was only these phonebook practice sheets that initiated a new direction in Wang’s artistic development, but his work began to take off in a variety of new directions, with calligraphy as the basis. The works in the current exhibition help to document his transformation from a Chinese landscape painter to a truly contemporary artist.

C.C.Wang (1907-2003), Lawn After the Rain in Cursive Script

Medium: Sponge painting brush with silver and gold color on black paper, double-sided framed

Signed Liao Ran Shu 了然书 on the front piece and Liao Ran Cao Shu 了然草书 on the back piece, with four artist’s seals.

C. C. began to explore writing with unusual materials in addition to the conventional Chinese brush and ink on xuan paper. He experimented with all kinds of of pens, felt markers, flat bristle brushes, and sponge painting brushes; he wrote with inks of different colors, on a variety of surfaces, including colored watercolor paper, and of course, pages from telephone directories! He wrote classical texts in white ink on black paper which, to Chinese viewers, are reminiscent of Song dynasty ink rubbings, but to an American audience look like chalk on a blackboard. He created double-sided images with writing on both the front and back of a sheet of colored paper.

C.C.Wang (1907-2003), Azure Dragon Cursive Script ,

Medium: Sponge painting brush with silver and gold color on black paper, double-sided framed,

Signed Liaoran 了然 on the front piece and, Dated jiaxu (chudong )甲戌(初冬)(Early Winter) in 1994 on the back piece, in total with four artist’s seals.

These calligraphic works reveal a part of C. C. Wang’s personality that is rarely seen in his later landscapes, which often convey a feeling of majesty and grandeur. C. C. was serious about his art, of course, but there was also a playful quality, and childlike curiosity about him that is wonderfully manifested in these carefree, joyful calligraphic expressions.

The works in the current exhibition demonstrate, even more than his most innovative landscape paintings, the extent to which C. C. Wang’s work was influenced by his environment. Because he lived in New York for five decades, even if he was more of a bystander than an active participant, he had witnessed at firsthand developments in the art world, including Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting, Pop Art, Minimalism, Photorealism, Pattern and Decoration, and every other important art movement.

Book cover: Spraycan Art and Subway Art

But it wasn’t just what was happening in the museums and galleries that affected him. Even street art did not go unnoticed. I remember showing him two books on graffiti that I had bought for my son, who was a teenager at the time, Subway Art[15], and Spraycan Art.[16] C. C. was fascinated by these images, many of which took the form of stylized lettering written with spray paint—a type of urban calligraphy using the written word as the basis for personalized graphic designs. These images or “tags” were ubiquitous in New York City in the 1980s. Subway cars were plastered with writing, inside and out, and virtually every unguarded blank wall became a canvas for renegade street artists. The unique sights and sounds of the city were unavoidable. Though thankfully Wang avoided vandalizing public property, the quick pace and frenetic energy of New York and its inhabitants are similarly reflected in the meandering lines and agitated rhythms of his late calligraphic works.

C.C.Wang (1907-2003), Homecoming (Gui Qu Lai Xi Ci) Cursive Script

Medium: sponge painting brush with silver pigment on blue paper, framed, With four seals of the artist

The literary content of these images was secondary, even irrelevant, to their visual impact. He transcribed well known essays, such as the Lanting Preface, and classic poems like Tao Yuanming’s “Homecoming” (歸去來辭) or sampled simple phrases from famous texts, like xiongzhong qiuhuo (胸中丘壑, “Mountains of the Mind”) and wrote them out in exaggerated script styles. Sometimes the tangle of brushstrokes resembled characters but had no meaning at all. Like a contemporary jazz musician, C. C. Wang took the poetic rhymes of his youth, added a touch of Hip Hop, and reconfigured them to match the dynamic rhythms of his late years.

C.C.Wang (1907-2003), Intricate Thoughts in Mind (Xiongzhong Qiuhuo) Running Script

Medium: Flat bristle brush with black ink on red cardboard paper, framed, Signed Ji Qian 己千 , dated jiaxu 甲戌 1994

Throughout his entire life C. C. Wang remained proud of his Chinese heritage and the artistic legacy out of which he grew, but after living in the Big Apple for more than fifty years, he was also a true New Yorker. What could be more representative of New York than a line of poetry scribbled onto a page from a Manhattan phone book?

[1] See: Jerome Silbergeld, Mind Landscapes: The Paintings of C. C. Wang (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1987). Ming Hua, Bridging the Tradition to the Modern the East to the West: C. C. Wang and His Life in Art, Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University, December 2014.

[2] C. C. Wang and Victoria Contag, Seals of Chinese Painters and Collectors of the Ming and Ch’ing Periods 明清畫家印鑑 (1940; repr., Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1966).

[3] Silbergeld mis-identifies this artist as Chang Tsung-jen “a French watercolor painter whom he knew only by his Chinese name” in Mind Landscapes, p. 21. Ming Hua repeats this error in her dissertation.

[4] Lois Katz and C. C. Wang, Mountains of the Mind: The Landscapes of C. C. Wang (Washington D.C.: A. M. Sackler Foundation, 1977).

[5] Arnold Chang, “C. C. Wang at Ninety: A Kaikodo Celebration,” Kaikodo Journal III (Spring 1997), pp. 10-11.

[6] MIng Hua, Bridging, p. 229.

[7] Ibid., p. 230.

[8] Silbergeld Mind Landscapes, p. 44

[9] James Silbergeld, C. C. Wang, The Lyrical Brush of C. C. Wang (Hong Kong: Plum Blossoms, 2001), p. 8.

[10] James Cahill, “A ‘Late Period’ for C. C. Wang” in C. C. Wang, Living Masters: Recent Painting by C. C. Wang(Hong Kong: C. C. Wang, 1996).

[11] Silbergeld,The Lyrical Brush

[12] Joan Stanley-Baker, “C C Wang and the Rebirth of Painting and Calligraphy,” in The Exhibition of C. C. Wang (Taipei Fine Arts Museum: Taibei Shili meishuguan, 1994), pp. 9-10.

[13] Chang, Kaikodo Journal III, p. 15-16.

[14] ibid., p. 16

[15] Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant, Subway Art, (Thames and Hudson, 1984).

[16] Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff, Spraycan Art, (Thames and Hudson, 1987).